The Changing Face Of Boldt On Decision’s 50th Anniversary

Congratulations, fish and wildlife reformists, you’ve somehow managed to align Washington anglers and hunters firmly with the tribes.

True, it’s a natural match, but wasn’t always so. Far from it.

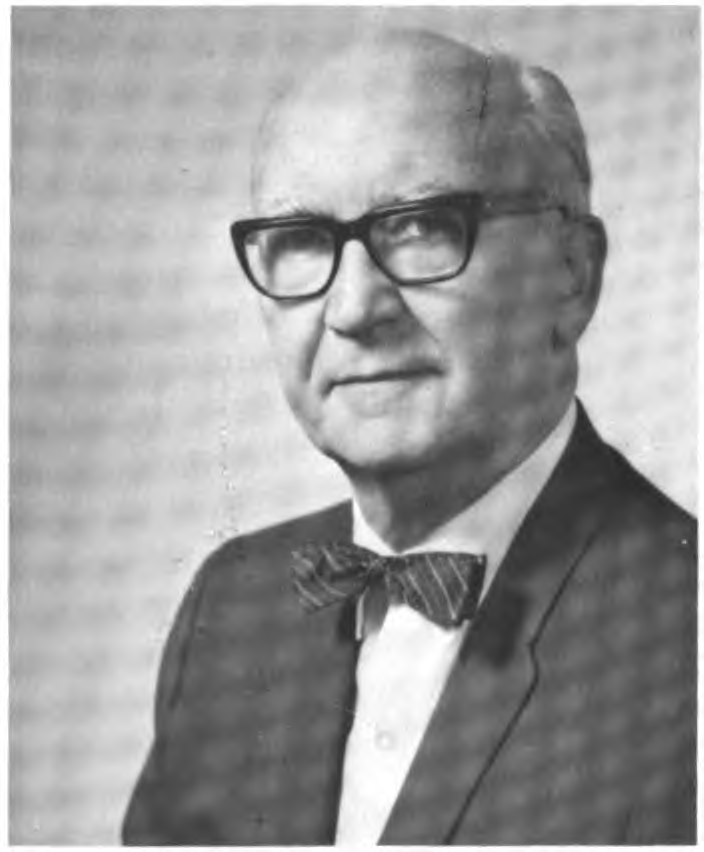

Today marks the 50th anniversary of the momentous Boldt Decision, when US District Court Judge George Hugo Boldt affirmed tribal treaty-reserved fishing rights to half the harvestable salmon and steelhead, a ruling that was ultimately upheld by the Supreme Court of the United States.

It followed on the so-called Fish Wars, when the state of Washington actively suppressed those rights.

“The predecessor agencies of the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, the Washington Department of Fisheries and the Washington Department of Game, fought, persecuted, and acted abhorrently toward the treaty tribes as they exercised their off-reservation treaty fishing right – an embarrassing and shameful chapter of my agency’s otherwise proud and rich legacy,” WDFW Director Kelly Susewind acknowledged in a special statement out this afternoon.

It wasn’t just the state.

In the decades afterwards, Boldt was not exactly welcomed with open arms by sportsfishermen and others worried about catching fewer fish. If I had a nickel for every time I’ve heard or seen someone blame tribal gillnets for the catastrophic, all-encompassing habitat alterations, overharvest and official government policies that since the mid-1800s have actually affected fish numbers far, far more, I would be a rich man and not have to blog one single word more.

But these days I feel like there’s a far better understanding among us and a burgeoning common purpose around protecting and restoring fish and their habitats, as well as providing and maintaining meaningful harvest opportunities and connections to the resources for all.

“Today, the tribes are leaders in salmon recovery and fisheries science,” Susewind’s statement continues. “The partnerships and strong alliances that have emerged from the profound, landmark Boldt decision are reinforced every day as we work toward our shared goal of recovering salmon and ensuring healthy and robust salmon populations are available for sustainable harvest for all generations to come.”

No, things aren’t all hunky-dory between tribes, WDFW and sportsmen. In the 10 years since I last specifically wrote about Boldt, I’ve reported a number of stories that have shown we’re not always on the same page.

Access to the Skokomish River. The Point No Point not-ramp. Grays Harbor coho and then steelhead. Anglers filing in federal court to become a part to Boldt. The Fish and Wildlife Commission’s Conservation Policy.

It’s that last one – the Conservation Policy – that has produced the aforementioned very notable recent shift, in my mind.

As you’ve read about it on this blog since September 2021’s introduction, some members of the Fish and Wildlife Commission want to put in place overarching policy guidance for how WDFW manages fish and other natural resources, which it does so with the tribes – comanagement – among other things, as well as come up with a new definition of the word “conservation.”

It took awhile for the policy’s proponents to fold in a “tribal considerations” paragraph into their relatively brief document, and while WDFW staff also recommended holding meetings with tribes before the commission made a final decision later this year, that counsel was called “absolutely absurd” by Commissioner Melanie Rowland of Twisp, so the citizen panel went damn-the-torpedoes-full-speed-ahead toward a late January vote.

That’s when the attorneys got involved and half a dozen Western Washington tribes formally demanded government-to-government consultations with the state on the “unilaterally developed policy,” and things came to an abrupt halt.

You will never in your lifetime see a commission reigned in more sharply, something a billion state hunter and angler comments could never have done on their own.

Nearly all of the tribes used the words “severe concerns” about the Conservation Policy, and all of them noted that the word conservation is already defined in United States vs. Washington, otherwise known as Boldt.

“It is inappropriate for the state to develop an ambiguous definition of conservation without engaging tribal co-managers as sovereigns,” the tribes stated.

To be clear, the tribes were acting to protect their treaty rights, but as the dust has settled, another interpretation of the judge’s ruling is taking hold.

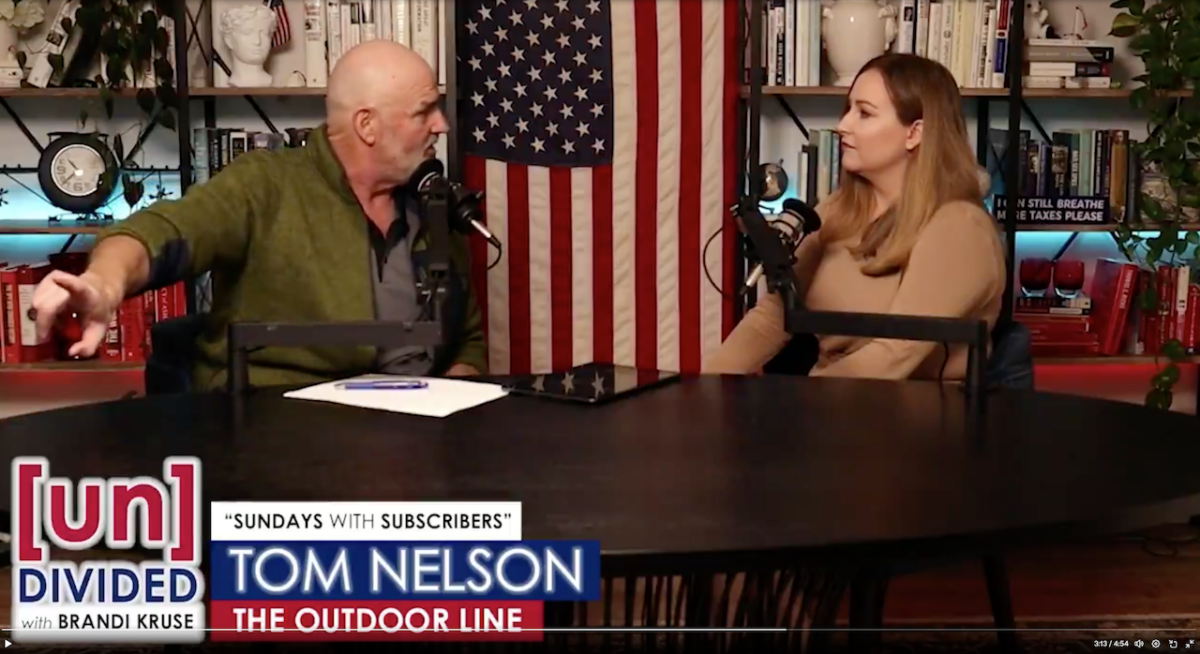

“When the Boldt Decision dropped in (1974), it was the seminal event that really drove a wedge between the tribal and nontribal outdoorspeople here in Washington. I understood that; I watched it happen; I was a little kid, but I still saw this, right,” Tom Nelson, host of The Outdoor Line on Seattle’s 710 ESPN, said recently on the [Un]Divided podcast. “Now the Boldt Decision has different implications, because now with this action, the tribes have demonstrated that their Boldt Decision is actually our Boldt Decision now.”

“Come full circle,” summarized host Brandi Kruse.

Tweeted Washington Representative JT Wilcox (R-Yelm) on today’s anniversary, “I’m from the generation that thought this was a disaster & now many of us recognize that without Boldt & without tribes there would be few fish for any of us. Boldt forced the states to preserve salmon so that tribal & non tribal fishing peoples could express their own cultures.”

Wilcox is also the author of a “hand grenade” of a bill that would do away with the Fish and Wildlife Commission, established by voter initiative in the early 1990s to put resource management above the political fray but which he suggests has been captured by Governor Jay Inslee, now in his third term, to the detriment of state-tribal relations.

“For a group of people who was supposedly vetted by the Governor’s Office, statements have come out over the last few months that make it plain that they have great scorn for their obligation to consult with tribes and it’s as if they don’t understand that the Boldt Decision is a thing that is binding on them,” Wilcox stated on Fish Hunt Northwest last Thursday evening. “I cannot believe the Governor’s Office and they would be so careless as to misunderstand that is one of the major safeguards we have providing opportunities to hunt and fish and they’re bound by the Supreme Court of the United States to pay attention to that.”

Nelson’s term for the commission was even more pointed: “a body of arrogance.”

One of the chief proponents of the Conservation Policy has been Commissioner Rowland, a retired federal ESA attorney, and last month she took exception to it being put on pause by the tribes, a “precedent that is totally open-ended in terms of our workload and how often we will need to do this.”

“Are we going to have independent tribal consultation processes with every policy, rule, guidance – I mean, whatever we vote on?” Rowland asked.

A response came the next day from Lisa Wilson of the Lummi Nation.

“You’re damn right,” she said to the commission’s face. “If it affects our treaty rights, it has to be consultation.”

Rowland’s question is a “pertinent” one, in the opinion of a learned observer who follows these sorts of things, but for the state of Washington – which has a history of losing in court when it comes to treaty rights cases – what new pain will this lead to?

Even as I’m proud of my reporting over the past decade on the aforementioned tough state and tribal disagreements – those stories are incredibly difficult to write – I’m just as proud of a piece I did on Ron Garner in the days leading up to Boldt‘s 46th anniversary.

Garner is the state board president of Puget Sound Anglers who literally waded into the Stillaguamish to lend his strength and voice to common cause with the Stillaguamish Tribe – restoring the troubled river’s habitat and its salmon runs.

“We’ve been fighting over the last fish for far too long and it hasn’t worked,” Garner said in Lifeblood, a 20-minute WDFW video highlighting how sportfishermen, tribes, farmers and others were working on the effort. “We used to fight with the tribes constantly. Finger-pointing, blaming. We don’t want to do that anymore, we want to bring our salmon runs back.”

To be clear, nowhere may be harder to do that than the Stillaguamish, but it set an example by leadership and was emblematic of the overall changing and softening tone critically needed now more than ever to better work together around shared interests and goals, and makes it among the big changes since the 40th anniversary, if we’re looking at things in 10-year increments.

“The sad fact is,” The Outdoor Line‘s Nelson told Brandi Kruse, “the hunters and fishers of this state, and indeed the rest of the nation, we hold the animals and the habitat in the highest regard of 90 percent of the people driving up and down I-5, and we share this attitude with the tribes because it is part of their culture and part of their heritage, Brandi, and it’s part of mine. I would not know how to exist on this planet if I couldn’t hunt and fish. I wouldn’t know what to eat.”

The camaraderie and good feelings may only last a little while – North of Falcon, which came out of Boldt and is the annual divvying up of the harvestable catch, is coming up quick – but I for one am very interested to see where things go from here and stand at the 60th anniversary of Boldt. I hope to report back to you then.

And that is going to have to be all the time I have for this.