Washington Coast Winter Steelhead Forecasts Out

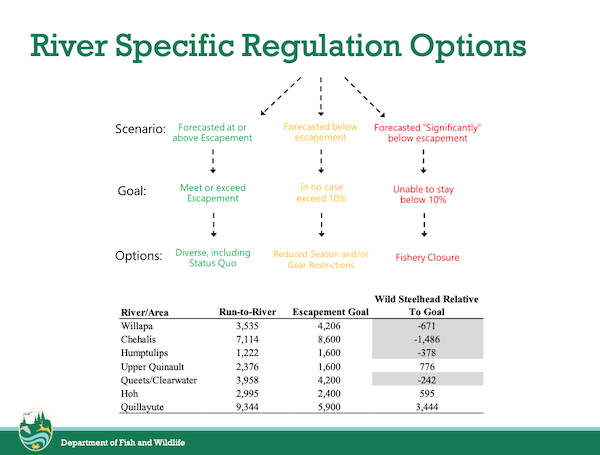

Washington wild steelhead managers expect coastal runs to continue an overall slow rebound from rock bottom this coming winter and spring, but four rivers are forecast to remain below escapement goals and might be closed, if recent seasons are any indication.

That quartet includes the Willapa, Chehalis, Humptulips and Queets-Clearwater, while the Quillayute, Hoh and Upper Quinault are all expected to handily meet spawning escapement needs.

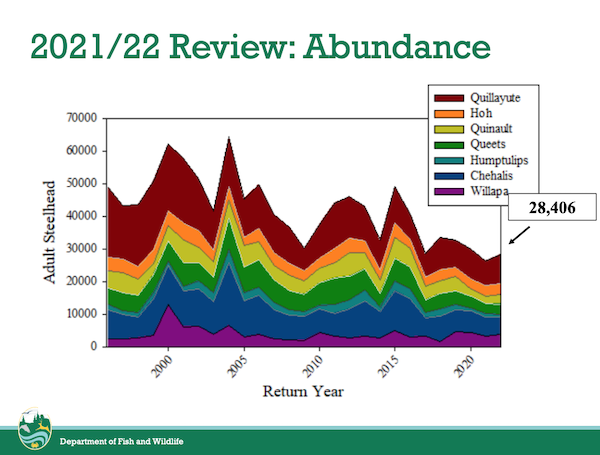

WDFW revealed the preliminary 2022-23 forecasts last night during a two-plus-hour Zoom-based town hall and presentation. They say coastwide, some 30,544 wild winters are coming back, which is an improvement on 2021-22’s 28,406 and 2020-21’s record-low 25,723. By comparison, high mark in recent years is just under 50,000 in 2015, the year of The Blob, which starved streams of snowpack-fueled runoff, and two years this millennium saw 60,000-plus fish.

The release of the forecasts is part of an ongoing public process that also includes input from anglers, guides, communities and other stakeholders and will culminate after Thanksgiving with a decision on this coming season. Early options WDFW showed range from a coastwide closure to last year’s regs with fewer days on the water to hatchery- and salmon-directed fisheries in specific waters.

Indeed, one of the rubs again will be whether plentiful hatchery fish can be fished for on slivers of systems that are otherwise expected to be below escapement.

For example, last winter saw nearly 3,800 clipped steelhead return to the Skookumchuck, a tributary of the entirely closed Chehalis watershed, with nearly 2,300 of those fish surplussed to local lakes and tribal and non-tribal food banks; 1,002 returned to the Humptulips, which was also closed, and 600 fish were surplussed from it.

Not being able to access hatchery steelhead in rivers – where they are meant to be fished for – calls into question the point of even rearing them in the first place, though I suppose it might be cheaper to let the ocean rear them to the same size if fishing in lakes for metalheads becomes a bigger thing.

WDFW regional fisheries manager James Losee said the agency is trying to figure out how to access hatchery fish and get them onto anglers’ grills instead of surplussing them.

The situation with Washington’s coastal wild steelhead fisheries hasn’t been good in recent years. Biologists blame a mix of poor freshwater and ocean conditions that have combined to impact multiple year-classes. They also now project that high-seas habitat in the North Pacific will continue to shrink due to a warming ocean.

In response, WDFW imposed unprecedented angling restrictions the last two seasons, including blanket no-fishing-from-a-boat regs and bait bans, among other measures, in 2020-21.

Last winter saw fishing completely closed on the Chehalis, Humptulips, Queets-Clearwater and Quinault because they were expected to be below escapement goals, but boats were allowed on portions of the Quillayute system, while anglers could bank fish the Hoh and Willapa system rivers.

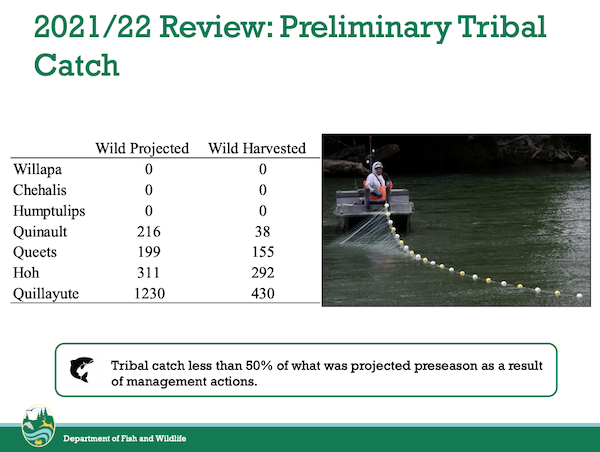

Yes, tribal fisheries have also been reduced, according to a rare glimpse of data WDFW was allowed to share last night. Tribes such as the Quinaults and Quileutes either completely curtailed or severely cut their gillnetting last winter, with catches coming in at less than 50 percent of what had been projected before the season began, last night’s state presentation showed.

At the peak, 152 participants were tuned into WDFW’s Thursday night Zoom meeting. They shared a mix of proposals, questions and flat-out frustration with the agency.

Among the latter category was Ravae O’Leary of Angler’s Obsession fly fishing guide service in Forks, who reminded state managers they had closed fishing early last season, chopping off March, and how were they going to fix it this season? At the time, WDFW’s fear was that far fewer wild steelhead were returning than forecast, but ultimately more actually did, though not by much. Still, it helped WDFW’s coastwide preseason forecast to come within 5 percent of how many fish actually showed up on the gravel. Declines continued on the Chehalis, though.

This year’s Quillayute forecast is again the strongest on the coast, 9,344, which is 3,444 fish above escapement needs. That would provide plenty of cushion for fishery impacts. For runs coming in below spawning needs, WDFW pulls out its statewide steelhead management plan guidance and looks at whether impacts can be kept at 10 percent of the run or less by restricting gear or days on the water. If not, a closure is called for.

There were also calls to keep systems with late salmon runs open and to open the upper end of the Skookumchuck for steelhead; claims that Wild Fish Conservancy – which is petitioning the National Marine Fisheries Service to list Olympic Peninsula steelhead as endangered or threatened – is leading the conversation; and requests for Oregon-style broodstock programs.

“I took a whole bunch of notes,” stated Kelly Cunningham, WDFW’s Fish Program manager.

Other portions of the presentation detailed return timing of the Chehalis Basin’s myriad runs; longterm smolt productivity of one of its stocks, Bingham Creek; a measure of run diversity within watersheds; longterm adult returns for the Puyallup and Nisqually; and ocean indicators.

Cunningham also encouraged attendees to stay involved in the process.

Next up is a staff briefing of the Fish and Wildlife Commission’s Fish Committee on October 27, then a second town hall in early November to go over potential regs for this season.

Members of the Fish and Wildlife Commission will also briefed at several meetings next month, WDFW will sit down with tribal comanagers to finalize management plans for the season, and in late November there will be a third town hall before seasons are announced in December.