WA Coast Steelhead Options Refined; Calls For Full Closure

With WDFW narrowing in on river-specific regs for coastal winter steelhead fisheries, some anglers are urging the agency to just shut it all down for the season instead.

Both are in response to low forecasted returns on all streams between Forks and Naselle, but enough on several to offer some fishing opportunity.

What that might look like was rolled out last night during the third in a series of four virtual town halls as state steelhead managers folded angler ideas into the mix ahead of a final decision expected in a few weeks.

Those include allowing boat fishing again but on fewer days per week; allowing boat fishing on select river stretches; allowing boat fishing from sunrise to noon; and sticking with the boat fishing ban as well as reducing open days to one to three days a week.

Other possibilities include lowering the limit on hatchery steelhead or opening the season only during that part of the run, as well as last year’s blanket rules and a full closure.

“We could have kind of a suite of regulations and then we could have regs … that I haven’t thought of,” said James Losee, WDFW’s coastal steelhead manager, as he opened up Tuesday evening’s two-hour meeting (now posted to YouTube) held on Zoom to feedback from the 170 to 180 attendees.

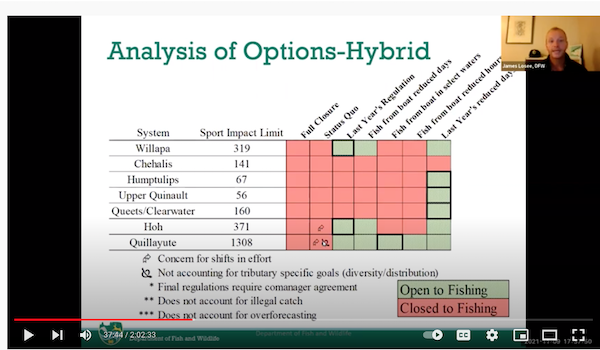

A red light-green light table Losee put together shows how a hybrid option with different restrictions for different waters would allow fishing in one form or another on all rivers except the Chehalis.

A hybrid option might see last year’s boat and bait bans reapplied on the Willapa and Hoh, those plus reduced days on the Humptulips, upper Quinault and Queets/Clearwater, and allowing boat fishing on specific parts of the Quillayute system.

That could let anglers plug and side drift for the most abundant hatchery forecasted return, the Bogachiel’s 4,169 clipped early-timed winter-runs, while providing opportunity and fish protections to varying degrees elsewhere.

“It’s important to note we are expecting hatchery returns to most of these rivers,” said Losee, referencing winter-runs produced mainly for harvest.

And it would give senior, disabled and youth anglers a stable platform to fish off of instead of the slick rocks of some Forks-area rivers, barred under last season’s sweeping, unprecedented bank-fishing-only regs.

In support of that proposal he made at late October’s town hall, angler Brian McLachlan pointed to part of WDFW’s legislative marching orders to the Fish and Wildlife Commission to “attempt to maximize the public recreational game fishing and hunting opportunities of all citizens, including juvenile, disabled, and senior citizens.”

“I think you need to provide opportunity to support your mandate,” McLachlan said.

While Garrett Moody saw a need to “leave the wild fish alone,” he also wanted to tap into hatchery steelhead – for example, the 2,169 expected back to the Skookumchuck. He called for the 1 mile of the Chehalis tributary below the hatchery to be open for that late-timed return.

Nathan Ereth was generally in favor of closing things down with the caveat of a compromise to allow fishing over hatchery fish through the end of December – their primary timing in his neck of the woods on the West End – that also came contingent with a call by him to hold a wider discussion about guiding in the state.

“James, if you guys give us something on the hatchery runs and you do no fishing from a boat on everything else … I guarantee you’ll get a different response from us. You’ll get a lot more open arms,” added Christian, last name unknown, but who said he had floated the rivers 150 times this year. “With the timing of those hatchery runs, I promise you we’ll be happy with something.”

But if it were up to the results of an online WDFW preference questionnaire and most anglers’ sentiments last night, it would be for a full coastal closure for the 2021-22 season.

That would be a harsh economic blow for towns like Forks during a slow time of year for tourism, but what might be necessary in the eyes of many to save this struggling crown jewel of the state’s faltering wild steelhead stocks – one of the last in Washington not listed under the federal Endangered Species Act.

“We’re kinda really missing the bigger picture here – I’m gonna keep banging the drum on that – we’re down to the last wild stocks that could maybe even potentially have a fishery compared to everything else that we’ve lost,” said Rich Simms, who at 64 years old said he’d never seen the runs struggling so hard.

“Until people realize that, I think we’re kinda sunk. We gotta do something drastic, in my opinion,” Simms added.

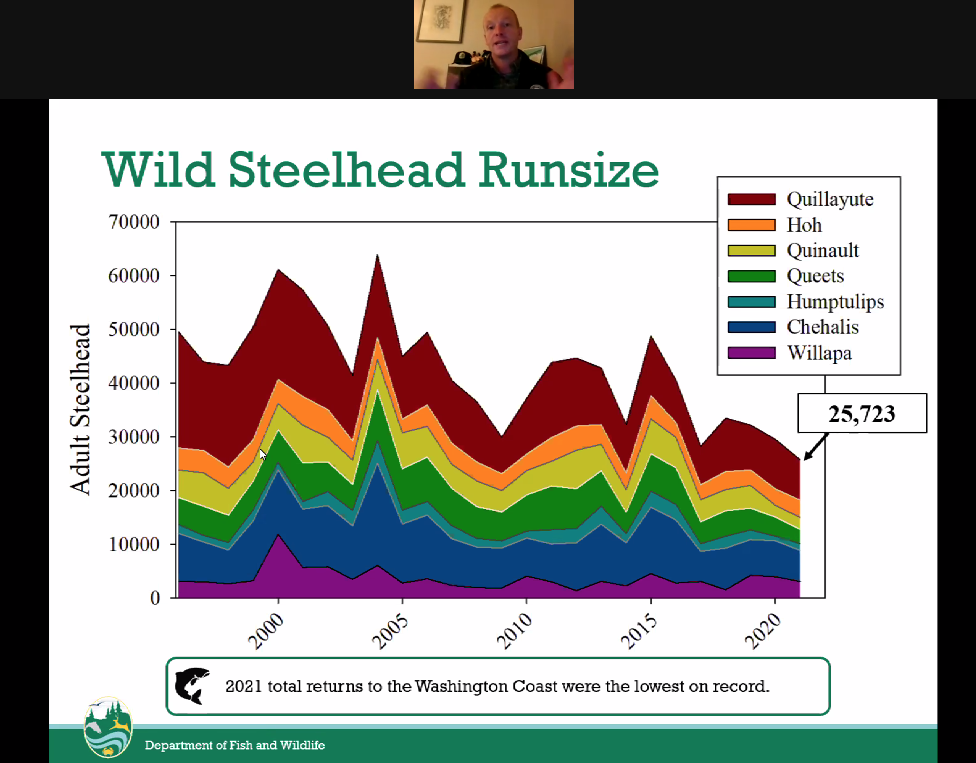

The 2020-21 total return of 25,723 wild steelhead to the coast was described as “the lowest on record,” with the Willapa, Chehalis, Humptulips, upper Quinault and Queets/Clearwater all coming in well below escapement goals, though the Hoh and Quillayute as a whole topped spawning marks.

The Chehalis in particular is struggling, with the 2021-22 return expected to be 2,900 fish below escapement goals with only 141 available for angler catch-and-release impacts. Fisheries are governed by WDFW’s statewide Steelhead Management Plan; for streams not expected to meet spawning escapement goals, there is a 10 percent mortality cap on sportfishing impacts

More tough years are ahead due to poor ocean conditions, WDFW warns.

“What the heck are we trying to do here?” wondered Jonathan Stumpf of Trout Unlimited.

He said he’d ask the commission and state legislators if what was being proposed given the run forecasts was in line with another WDFW mandate from lawmakers: “It calls for conservation first.”

A poll taken on WDFW’s website showed that 59 percent of 81 people wanted a full closure, while 27 percent supported last year’s blanket regulations, with 7 percent wanting to go back to the status quo rules in past years’ fishing pamphlets, 6 percent in favor of “diverse regulations,” meaning the hybrid option, and 1 percent in favor of an early closure.

Bridget Moran, who said she was on “hour 10 of Zoom meetings,” offered a more blunt take: “At this point it doesn’t [bleeping] matter what the people need, so just shut down the whole thing already.”

From her vantage near the Skagit River – the last wild winter-run option in Pugetropolis and highly regulated and monitored when open – she wasn’t interested in listening to moaning and groaning about possible restrictions on the coast.

“Give me a break,” she said, likening the debate to dogs fighting for the last scrap behind a fast food restaurant.

Pointing to longterm coastal declines, uncertainty over fishery impacts and the risk of overforecasting, steelhead researcher and angler John McMillan called for a full closure.

“For these reasons and others, I’m asking that we try and put a stop to this Groundhog Day, this kind of recurring nightmare where we wake up and think things are OK, because they’re not OK. And if we don’t take strong action this year, like a fishery closure, the next inevitable step is an ESA listing and continued interruptions to fisheries for the foreseeable future,” he said.

But Forks-based guide Ryan Bullock saw little hope that shutting everything down would do the fish any good.

“I guess I’ll buck the trend here and just bring up the fact that we’ve seen full closures not work in Puget Sound. We’ve seen full closures not work in a number of areas in reversing declines in steelhead numbers,” he said.

Once upon a time there were vibrant wild steelhead fisheries on the Skykomish, Puyallup, Green-Duwamish and Nisqually, but listed since 2007 they are now all but permanently closed to angling for nates as habitat, predation and ocean conditions throttle recovery.

Reduced and changing hatchery practices, along with lawsuits, have also left Pugetropolis’s consumptive steelhead fishery a shadow of a shadow, leaving anglers to go to coastal waters to get their kicks.

Bullock said that it was “really important” to keep anglers involved by providing fishing opportunity, as well as supplying fishery data for the state, and that there was “wiggle room” to do so on the Hoh and Quillayute.

“That’s getting lost on a lot of the people in the conservation community, that without anglers caring about these fish, they’re going to go away quicker,” he said.

A number of subsequent speakers who called for a full closure refuted that, vowing their work for the fish would continue.

A lot of questions circulated around whether a full closure meant no treaty netting too.

“I can’t get the tribes off the water, right, they manage their own fisheries,” Losee responded, “So I just want to make sure there’s a treaty right there that we’re all recognizing.

But he also noted that implementing a sport closure was a way “to signal our concern” to tribal comanagers.

And he also pointed out that some tribes are taking the lead on the issue, and in late October he reported that their harvest last season was “significantly lower than expected” as they, like WDFW, scaled back their fisheries in response to the low forecast.

There were also questions about WDFW data – both from guides in Forks who said in their time on the water they hardly if ever saw state spawning redd surveyors, and others who questioned the agency’s catch per unit effort estimates.

Indeed, where last month’s town hall presentation offered multiple pages related to Hoh River CPUEs from several seasons ago and WDFW’s extrapolation from it that the 2020-21 coastal catch was reduced by 56 percent by angling restrictions, they were missing entirely from last night’s.

That may have been just editing toward a more condensed presentation, but WDFW’s math has come under close scrutiny.

“A lot of people have brought this to our attention that this is a major limitation for our managing wild steelhead moving forward, and we’re agreeing and … highlighting that as one of the major limitations,” acknowledged Losee.

There’s also still no estimate for how many wild steelhead are being poached, nor can anybody agree on catch-and-release mortality rates or even egg loss.

McMillan stated that Atlantic salmon hens caught and released once were essentially only 73 percent as fecund; another angler replied that those fish were not in fact steelhead, nor here.

As it stands, the next steps are a joint WDFW-tribal comanager meeting to “finalize management plans that guide the approach to the 2021-2022 coastal steelhead season,” a November 17 briefing of the commission’s Fish Committee, a fourth town hall in late November to share the agreed-to fishing plan with the tribes, and a formal early December announcement on state fisheries.

But meanwhile, WDFW is still taking angler input. Last night Fish Program Director Kelly Cunningham continued to urge anglers to use wdfw.wa.gov/coastal-steelhead to provide feedback.