Last week I wrote that 32m was a pretty notable wolf, but at the time I didn’t know how truly that was the case.

My story focused on the longtime Teanaway breeding male living to the very old age for wolves of 12 and siring a number of litters as the “patriarch” of Central Washington’s first pack in 100 years before succumbing to natural causes near Ellensburg this summer.

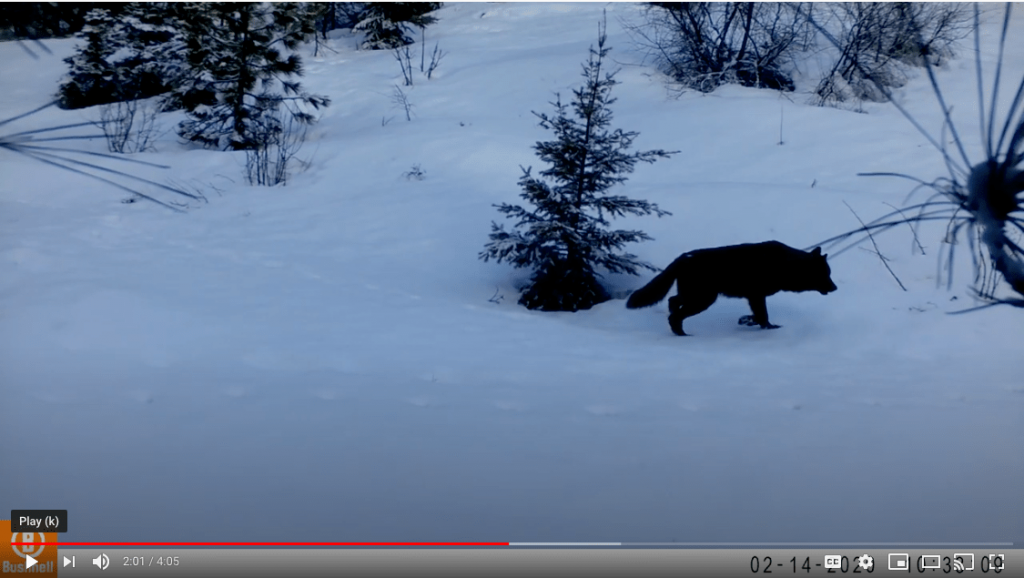

This week WDFW posted a video tribute to the animal.

But 32m is distinct for another reason: It was incestuous – and how.

It bred a sister and then two of their female pups, a rarity outside of isolated populations, and instructive about what has been until recently a dead end in Washington’s wolf world.

First, a little history about the original Teanaway Pack mates.

Both 32m and 012f were born to the Lookout wolves of the Methow Valley – at the time themselves relatively removed from packs in Canada and the Northern Rockies – with the male’s estimated age putting its birth in the same year as the pack was first confirmed, 2008.

That discovery kicked off years of WDFW capturing and collaring wolves as they bred and spread across Washington, efforts that also yielded biological samples.

The aforementioned video notes 32m was caught in 2013 (if not before), while 012f was trapped in 2011.

A 2017 WDFW genetics report reveals the relationship between the two and their parents.

“001f and 002m from Lookout have high relatedness values to 012f and 032m (r-values 0.44 to 0.60), which are consistent with a parent/offspring relationship. In addition there is only one genotype mismatch between each individual and the Lookout pair,” it reads.

Thirty-two-m and 012f settled in western Kittitas County, likely in 2010, and in 2011 were confirmed to have had a rather large litter, seven pups.

Notably, five were females.

“012f and 032m … produced 015f, 016f, 031f, 033m, 038f, 072f and M016-13WA. This is based on the high relatedness values (r-values 0.41 to 0.62) between these individuals,” the WDFW genetics report reads. “In addition there are zero genotype mismatches between 012f, 032m and 015f, 016f, 031f, 033m, 038f, 072f and M016-13WA, which means that 012f and 032m cannot be excluded as the parents. The pairing of 012f and 032m is an inbreeding event as the pair are full siblings.”

Sometime after having that big litter, 012f disappeared. Perhaps it died, maybe it was forced out of the pack or it could have wandered off on its own. Regardless, it was never seen again.

In stepped daughter 38f as the Teanaway’s new breeding female. It and 32m had at least one litter of four.

Again the genetics report links father, daughter-mother and their pups, as well as shows how increasingly inbred the pack was becoming.

“This is based on the high relatedness values (r-values 0.59 to 0.69) between 038f, 032m, 043f and 044m,” the report states.

“In addition, there are no genotype mismatches between 038f, 032m, 043f and 044m which means that 038f and 032m cannot be excluded as the parents. The pairing of 038f and 032m is also an inbreeding event as the pair are father and daughter,” it continues.

In fall 2014 word emerged that 38f had been illegally shot after its body was found near Salmon la Sac, northwest of Cle Elum and west of the Teanaway proper.

Despite the offer of a large reward – the poaching occurred in that part of Washington where wolves are still federally listed – the case remains unsolved.

Up stepped yet another daughter of 32m and 012f as the new breeding female, 072f. It was trapped and collared in 2017. At the end of that year there were eight Teanaway wolves.

Since then another female has apparently taken its place, but it hasn’t been captured, so its genetic background is unclear.

“It could have been a disperser from another pack. It could have been another pup (of 32m’s); that pattern is there,” said WDFW’s Staci Lehman in Spokane. “Until we collar her we won’t know.”

Regardless, the agency’s annual year-end wolf counts provide a rough idea of Teanaway Pack numbers over 32m’s, 012f’s, 038f’s, 072f’s and the new alpha female’s years:

7 wolves as of Dec. 31, 2011 (three adults, four pups);

6 at that same point in 2012 (four adults, two pups);

6 in 2013 (four adults, two pups);

5 in 2014 (two adults, three pups);

3 wolves in 2015 (adult and pups are no longer differentiated);

5 in 2016;

8 in 2017;

5 in 2018;

and 6 in 2019.

Though pup data is incomplete and to a degree this count is speculative, as the alpha male 32m would have accounted for somewhere around at least 20 young wolves that lived to see the depths of their first winter.

With 50 percent of juveniles routinely dying before then, 32m’s tally could be as high as 40, but that seems unlikely with inbreeding.

So why did 32m choose to mate with its sister and then its daughters?

Perhaps the exact opposite reason a Ruby Creek female in wolf-rich Northeast Washington decided to shack up with a local sheepdog – a lack of options.

“The Teanaway pack is the most geographically isolated pack in the state of Washington,” the genetics report notes.

Today, via Lehman, WDFW wolf biologist Trent Roussin told me it’s hard to know for sure why the inbreeding occurred, but he points to the relative lack of dispersers in the neighborhood — which may have also led to 32m’s long life of a dozen years.

Six to eight years is the average for wolves.

“In one respect, it is pretty common for breeders to remain breeders for multiple years, until they are pushed out or killed (often by other wolves). I have to assume that this applies regardless of any inbreeding potential. The fact that 32m never seemed to be challenged as a breeder might suggest that there were not many males coming through the Teanaway over that time frame and he was able to maintain his position until he was quite old,” he says.

“An overall lack of dispersers would also be consistent with the fact that he often bred females from within his own pack, even after breeding female turnover. This would suggest that there were not many females dispersing through either,” he adds.

In the Northern Rockies, male wolves represent around 57 percent of all dispersers, females 43 percent, but only 28 percent of dispersing males become breeders whereas 42 percent of wandering females do, according to research done by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Mike Jimenez and other scientists that Roussin cites.

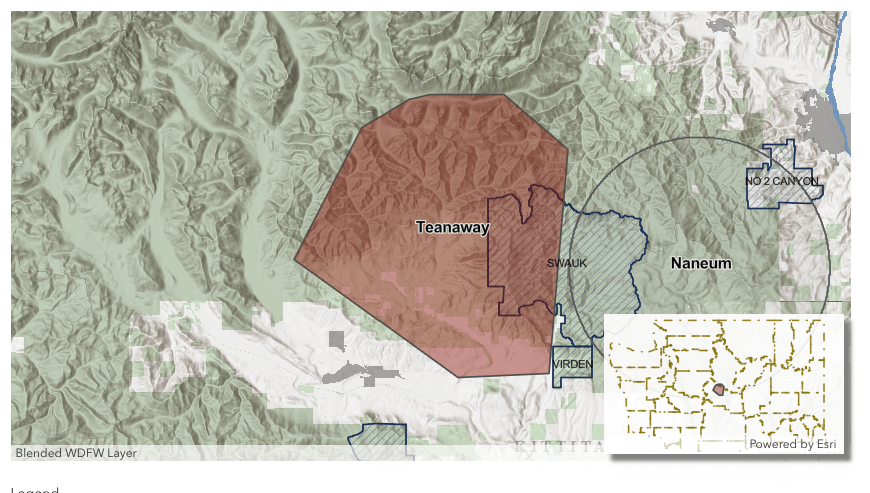

To be sure there have been confirmed wolves in these parts of Central Washington over the years – the old and short-lived Wenatchee Pack, one hit on I-90 west of Snoqualmie Pass, ones near Stevens Pass and in the Chiwaukums, now the Naneum Pack.

But the gene flow has otherwise been one-way traffic as evidenced by WDFW dispersal maps showing collared Teanaway wolves going due north up the east side of the Cascades into British Columbia.

Yes, there have been numerous public reports of wolves to the south of the Teanaways, but no packs have been confirmed between there and the Columbia by WDFW.

And what’s more, an intensive two-year survey using scat-sniffing dogs and lab analysis of 2,400 samples turned up zero groups of them, per a report last month.

It all suggests that the Teanaways are at the end of a road few wolves go down, for whatever reason.

In my nonscientific mind, it raises the question of whether translocation might have actually been a good idea to look into, and how wildly optimistic WDFW’s estimate that Washington could reach statewide wolf recovery goals as early as 2021 was.

I mean, the latter seemed legit in 2014 with the Teanaways perched on the edge of I-90 looking for a break in traffic to cross into the South Cascades and Olympic Coast Recovery Zone, the third of three regions requiring at least four successful pairs for statewide delisting.

Today, however …

So how incestuous are wolves?

A 1997 study by famed wolf researcher David Mech and others that looked at data from free-roaming populations in Alaska’s Denali National Park and northeastern Minnesota’s Superior National Forest found “mated wolves are rarely related as siblings or as parent-offspring.”

Wolves are pre-paw-sterously footloose, something that a few folks still don’t seem to grasp.

A Northeast Washington wolf traveled 700 miles to Central Montana before being killed. A Yellowstone wolf went 1,000 miles before landing in Colorado. That keeps Canis lupus genetics on the up and up.

But sometimes packs apparently get cut off from population sources for whatever reason.

Those that in 1948 went across the ice to colonize Isle Royale, in the middle of massive Lake Superior not far to the east of Minnesota, were so inbred by 2018 that they were down to just two animals.

And researchers found that some of the progeny of the few that colonized Norway and Sweden west of reindeer herding areas – which act as a barrier or sorts from Finnish and Russian populations – in the 1980s and ’90s and now number around 400 or so exhibit “extreme lack of genetic variation,” making them “more susceptible to genetic diseases and the species less adaptable overall.”

All that said, there is a new breeding male in the Teanaway, a black-coated wolf that arrived last winter and possibly led to an aged and increasingly frail 32m to depart the territory and slide into a spot between there and the Naneum Pack, where it died after siring a large number of pups with its sister and daughters and contributing an unusual chapter to the ongoing story of wolves in Washington.