UPDATED 5:15 P.M. SATURDAY, DECEMBER 10, 2022, BELOW THE BOLDED SUBHEAD TOWARDS THE BOTTOM

More collared Blue Mountains elk calves have survived to this point of 2022 than last year, but cougars are again taking the lion’s share among Southeast Washington’s burgeoning predator guild.

WDFW Region 1 Manager Steve Pozzanghera this morning in Clarkston reported to the Fish and Wildlife Commission that as of early December, 23 calves were still “on the air” and that 48 other collared calves had died, with 31 of the confirmed 37 predator mortalities attributed to the big cats – 83 percent.

The sample size of 73 collared calves means that survival among these young wapiti so far is 31.5 percent, versus just 9.4 percent at the same time last year.

WDFW was able to initially collar 102 calves for 2022’s study, but saw “significant issues” with the devices prematurely dropping off of 29 animals, leaving the 73, Pozzanghera reported.

Biologists had wanted to get collars onto 125 calves from this hard-bitten elk herd and were able to meet their benchmarks in two game management units but fell short in the third, Tucannon.

At pretty much the same time last year just 11 of 116 calves were still alive, sparking deep concern among harvesters and local producers because it was so far below replacement needs, meaning the herd then at a 30-plus-year low wasn’t able to rebuild itself following the harsh 2016-17 winter and predation, though some commissioners at the time were less concerned. State managers say 20 to 30 percent of elk calves need to survive to their first year for a herd just to hold steady.

In response to that dangerously low calf survival and verified deaths by cougars – which ultimately accounted for 74 percent of the 77 confirmed predator mortalities on 2021’s collared calves, with the rest attributed to wolves, bears, coyotes and bobcats – WDFW proposed and the commission voted 5-4 to allow hunters to take a second cat this season in several Blue Mountains units, though the overall quota remains the same.

But the commission has also repeatedly voted down the limited-entry spring black bear hunt in the Blues (and statewide) in 2022 and 2023, which could have mitigated bruin predation on elk calves. Some members say that if WDFW brings them a specific management-based spring bear proposal, they may consider it.

WDFW biologists will continue to track this year’s calf cohort through winter and the agency plans to perform the study again next spring.

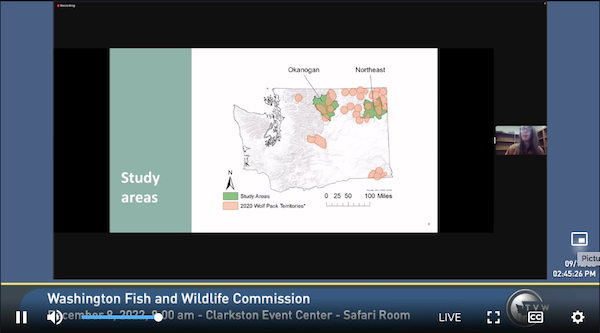

IN OTHER PREDATOR-PREY NEWS from December’s Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission meetings, more details finally emerged from the joint WDFW-University of Washington research into ungulate-carnivore interactions in the Okanogan and the state’s northeast corner, a legislatively funded effort.

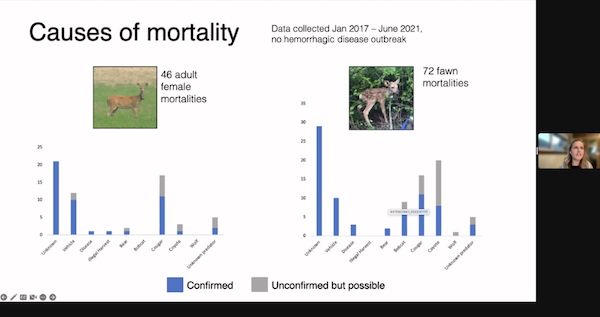

UW’s Taylor Ganz stated that Northeast Washington’s whitetail deer population appears to have been “declining a little bit” during the Predator Prey Project’s January 2017-June 2021 timeframe, a more definitive statement than was picked up earlier this year in a newspaper article in which she called it stable and which was published prior to a huge EHD outbreak. According to her research, the mean population growth in the region was .97, with whitetail doe survival estimated at 73 percent and fawn survival at 36 percent.

She said that of the 280 whitetails collared for the study, there were 118 mortalities, with “quite a lot” dying due to collisions with vehicles, while cougars were the “primary predator” for does. Fawns were killed by a variety of predators, stated Ganz, who added that winters had also been more severe than average across that timeframe.

She said that improved forage conditions could help the deer out, as could a smaller population of predators, although that might result in increasing competition among deer for browse. Reducing predators has been shown to provide a short-term benefit to ungulates.

On the elk side, Northeast Washington cows were surviving at a rate of 93 percent and dying primarily due to human causes – harvest (eight) and roadkills (three) – according to Ganz. In response to questions, she stated that it appeared that the study region’s elk seem to be “significantly increasing.”

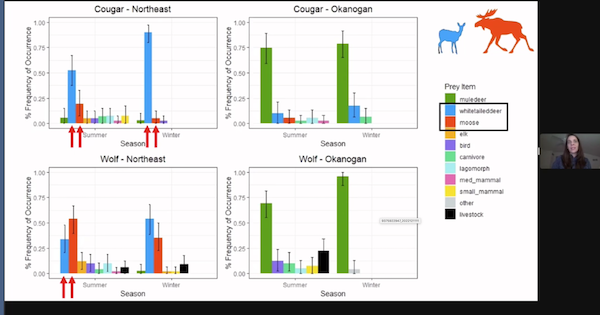

The UW’s Beth Gardner, summarizing researcher Lauren Satterfield’s work around scat samples, stated that there was a .75 to .95 dietary overlap between wolves and cougars in the Okanogan and Northeast Washington, with the overlap strongest in the former region and in winter there.

In western Okanogan County, mule deer are the preferred prey for both toothsome species, in the high season and in the dark.

In Northeast Washington, cougar doots show they mostly focus on whitetail deer in summer and winter, while wolves seesaw between moose and flagtails from summer to winter, respectively.

One of the more interesting results from UW’s Sarah Bassing revolved around how humans affect both predators and prey. It will be no surprise whatsoever to hunters, but the researchers’ collared deer were less likely to be on public land during fall’s season and more likely to be on private, while at the same time predators were “willing to risk being closer to hunters,” likely for the potential payoff in the form of a gut pile, a factor that those who pursue big game in grizzly country may be familiar with.

In other news from the commission meeting, during public comment there was pushback on WDFW buying more local land due to concerns around weed control, land management and impacts on ranchers and farmers. It came in response to the agency’s acquisition proposals for the coming budget biennium.

Just as in Colville earlier this fall, there were also local concerns expressed about predator numbers and Blue Mountain elk herd declines. Asotin County rancher Jay Holzmiller expressed a lot of frustration around decisions by his former colleagues around bear and cougar management in the Blues and he went “really redneck” with some comments around the relative ease of poisoning canines while stating he wasn’t going to give up his spread.

It was verbiage that may end up in anti-hunting propoganda, as one meeting observer told me; it underscores the critical importance of local social acceptance around wildlife management, spun another.

In response to other public comments, Commissioner Melanie Rowland, a retired federal attorney who moved to Twisp, admitted that during a closed-for-comment decision in November on spring bear hunting she had received “a text from someone … a friend” that reshaped a motion on the floor that the commission didn’t approve of a recreational hunt for spring bears. She acknowledged it was a violation of commission policy but that she didn’t believe it was a legal violation, rather a “harmless error.”

That was after outgoing Commissioner Don McIsaac stated it had created a “for cause” litigation risk. He added that it would be up to someone on the prevailing side of last month’s spring bear vote to bring a hunt back up for another go, as it didn’t appear to be on 2023’s year-at-a-glance calendar.

Commissioner John Lehmkuhl, in the other camp, indicated that the spring bear decision didn’t preclude WDFW from bringing a hunting proposal forward, whether to manage timber damage or to mitigate elk calf predation, thus the door is still open.

McIsaac – a process stickler to the nth degree – retorted that the language in the actual motion that passed did not specifically address doing so for management objectives. A WDFW press release on the result suggested there was wiggle room, even if it was not spelled out in the amended motion.

Speaking of McIsaac, today was his last action on the commission, as he has resigned rather than apply to extend his term, which ends New Year’s Eve. Throughout this week’s meetings the rural Clark County resident and longtime head of the Pacific Fisheries Management Council received hat tips and kudos for his work on the citizen panel that oversees WDFW policy and hires and fires its director.

And that is all the time I have for all of this.