Rough Days At Sea Series I: High Pressure At The High Spot

A run out to the South Coast halibut grounds in an open-bow boat nearly turns disastrous for Oregon anglers when a storm hits.

Editor’s note: This is the first in a series of stories from Coos Bay-area angler Jim Pex.

By Jim Pex

Going out on the ocean in a small boat is not much different than hiking into a wilderness area. You never know what you might see or what unique experiences await you. Like the wilderness, one does not go to sea unprepared, nor does one venture forth without a guide or some personal experience. When things go wrong and you’re not ready for them, it can be lonely out there, putting your life and those with you in danger. Ancient mariners were well aware of the dangers and risked their lives based on their personal skills.

The ocean is mysterious in that conditions change from day to day, sometimes from moment to moment. There is a thrill in going out there and dealing with the unknowns that come your way. But beware, your primary resource, the weatherman, may not be your friend.

About 10 years back, I had a friend named Jim who was running a guide service on the ocean. It usually was for rockfish and he only ran out a few miles from the safety of the bar and the inner bay. He had a 22-foot aluminum boat with an open bow that was not built for rough ocean conditions, but on a good day was certainly adequate. The boat had a large motor as the main and a smaller one for trolling or just backup.

My friend had taken the Coast Guard classes and had what we call a six-pack license to take up to six people fishing. Getting the license requires passing an exam, so the expectation is that the licensed captain knows what he or she is doing. Jim had been out on the pond on a number of occasions, so we thought he was capable. In talking to him, you could tell he was confident of his skills out there.

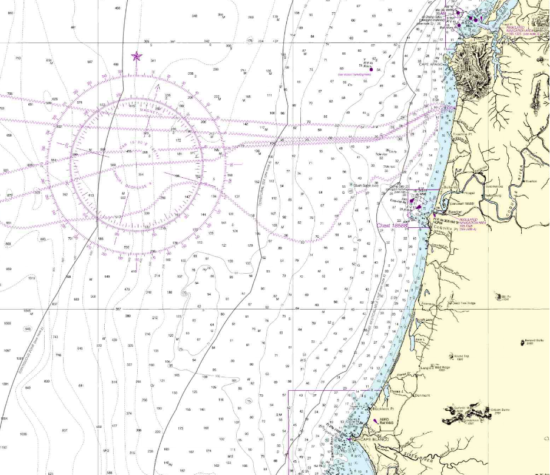

JIM GOT A CALL FROM A CLIENT who wanted to catch a halibut. The best place to do so in our area is called the Bandon High Spot. This is an underwater plateau located between Bandon and Port Orford and about 15 miles west from shore. The bottom rises from 700 to 800 feet deep to 400 to 500 feet deep. It is a hangout for large halibut and a great spot to fish, if you can get there.

The downside is that it is distant from any support such as the Coast Guard or a safe harbor. Unlike on land, there are no roads, no tow trucks and no immediate help if things go wrong at sea. If you capsize out there, it is unlikely anyone is going to find you until much later.

The front of the high spot from the Coos Bay bar is south, 27 miles distant. It is 15 miles south of Bandon and about the same distance from Port Orford. Bandon is not much of a refuge if things go wrong since it is difficult to get across the bar most of the time. Port Orford is OK but there is no trailer boat launch; you need to have your boat lifted on and off the water with a large crane, provided you have the appropriate straps.

CHECKING THE WEATHER, IT LOOKED TO BE sunny with a light wind out of the north when Jim started for the Bandon High Spot. Waves were forecast to be 3 to 4 feet, not a bad day to go fishing. Actually, it was about as good as it ever gets out there. Another friend named Leonard was also on board for this trip as a deckhand. The rest of this story is based on what Leonard told me weeks later.

Jim left the Charleston harbor at daylight and made the 27-mile run downwind to the High Spot. Since he was running with the wind and waves, the trip was comfortable and made at good speed. They arrived about an hour and a half later and there were a few other boats around. It is good to have a little company when you are this far from home.

Fishing 500 feet down with a hand-crank reel is a test of one’s endurance. To get to the bottom requires 2 pounds of weight off the end of a stiff rod. Herring is usually the bait of choice. Leonard said fishing was slow that day but they managed to get their limit of three halibut over several hours.

By that time the other boats were gone. As Jim, Leonard and their client had fished, the wind had increased and the waves doubled in size. In nautical slang, “The sheep was on the water” by the time they wanted to leave. This means there were whitecaps on the waves from the wind. In this case, the wind was straight out of the north, the waves from the northwest. Getting back to Charleston meant heading north into the seas and wind.

Jim finally shipped the rods and tackle and told the others to sit tight for the trip back home. He said it looked like it might be lumpy and slow; four to five hours of running was a possibility. He turned the boat into the seas, pushed the throttle but could make very little headway at displacement speed without shipping water over the bow. Keep in mind this boat had an open bow that was very slow to drain when taking water. It seems they never make the bow scuppers large enough in these boats; I think they were designed for rain, not waves.

GETTING ON PLANE DID NOT SEEM LIKE A possibility and a long trip home was becoming more realistic. However, there is a technique in which one can put the power to the throttle and get up on top of the waves and basically run from wave top to wave top, but the conditions must be just right. Jim knew this and decided to give it more gas.

He hit the throttle and got on top of the first wave – and immediately launched the boat into the air like a water skier flying off a jump. The boat came down hard, knocking the other two to the floor. Undaunted, he kept on and plowed the center of the next wave instead of going over it. That wave came over the bow and filled the open bow with water, making the boat front heavy.

Jim apparently panicked and pushed the throttle harder and took another wave head on. This wave was higher than the windshield and passed over the heavy bow. It struck the windshield with such force that it knocked the glass out of the frames. Then as the green water passed through, water and windshield took out all of his dash electronics. Finally, as the moving wall of water passed along the boat, it struck the three people on board. Jim was hit first, by the glass and water, and was momentarily dazed. He had a hold of the steering wheel but the other two were less prepared and were carried by the water. The client nearly went over the side but managed to grasp a seat back with one hand while balancing on the gunnel. He hung on well enough to get back in the boat. Leonard was carried by the wave to the rear engines and did a face plant into the main motor. He was momentarily knocked senseless and the engine was all that kept him in the boat. He said he probably had “130” imprinted on his forehead from the emblem on the motor. All three were now soaked and frightened. None had experienced anything like this.

Jim backed off on the throttle as the wave passed through. Now they were at idle with a load of water sloshing back and forth inside the boat. Everything was floating and other waves were lapping at the sides as they tried to regroup. On the boat, the distance between the waves and the top of the boat sides is called the freeboard. Freeboard went from a couple feet to just inches with all that water on board. Fortunately, a few buckets were floating around and so they started to bail. The boat was now sideways to the oncoming waves and rocking violently as the crew gathered themselves. The vessel did have a bilge pump, but this was way beyond what the small unit could handle.

Since there were no longer any other boats in the vicinity, Jim quickly grabbed the VHF mic and tried to hail the Coast Guard, shouting “Mayday, mayday!” But there was no response as the radio was dead and the antenna was gone. Their cell phones were also wet, and out of range anyway.

Using buckets, the client and Leonard bailed water as Jim turned the boat south for a slight reprieve from the rising seas. They were alone, sea conditions were worsening, they had no radio to obtain help and their navigation instruments were dead also. There was not so much as a hand-held compass on board for guidance. If they took on any more water, they could capsize. And with land at least 15 miles away, no one would consider them missing for several hours. A life jacket was of little value when hypothermia in these cold waters was the Devil. Imminent death by drowning was racing through their minds. Was this it? Were they going to die? In this moment of terror, there was an upside: the engine was still running, and they were still afloat.

TO MAKE MATTERS WORSE, THOUGH, THE FOG was beginning to set in up north, so the decision was made to run for Port Orford. They could see Humbug Mountain and Orford Rocks to the east and knew Port Orford was over there somewhere. Jim had never been there from the seaward side, so he pointed the boat in that direction, thus making some headway in the wind while the waves lapped at the boat’s port side. At least they were underway despite not knowing for sure where they were going or if conditions might change before they got there.

As Jim steered, the other two continued to bail water. They were all cold, wet and fearful as the seas continued to whitecap. Yet their situation slowly improved as they continued to bail water. The trip in seemed impossibly slow.

When they got closer to shore, the sea conditions improved, and they recognized what they though must be Orford Rocks and knew the port was somewhere around there. Everyone got excited when they spotted a boat fishing the reef near the rocks. They approached while making the emergency signal, raising both hands above their head and crossing them back and forth. I was in that boat fishing the reef. I saw the signal and recognized their boat.

“This is weird,” I thought. “Where did they come from?”

I hadn’t seen their rig at the dock when we’d launched.

Jim came close enough to me that I could shout directions for getting to Port Orford. I also made eye contact with Leonard. I would bet that if he thought there was any way he could have gotten off that boat and onto mine, he would have jumped. I did not know the client but he looked like he had literally escaped death. His clothes were soaked and disheveled, his hat was gone and his expression was grim.

Jim and his crew made it to the port. It was what we seafarers call a “kiss the dock moment.” They had to tie up until they could reach Jim’s wife, who retrieved the truck and trailer in Charleston and brought it the 50 miles down to Port Orford.

Again, the port doesn’t have a regular boat launch. Vessels have to be lifted in and out with a crane. By the time Jim’s wife arrived, it was dark and someone lent them some straps to get their boat out of the water.

For all the effort and terrifying moments at sea, they were no longer in possession of the halibut, as the ice chest with the fish had gone overboard when the wave had passed through the boat.

THE OCEAN IS A BEAUTIFUL PLACE TO FISH on a good day. But conditions can change in a hurry. It is up to the captain to recognize the changes and respond based on the kind of boat and his boating skills. Despite the conditions, Jim was successful in getting himself, his crew and his boat to safety. He eventually got his boat fixed and had enough wisdom to never go back to the Bandon High Spot again with it.

One thing is for certain: If you survive these kinds of wilderness experiences, it makes you a whole bunch smarter. The upside from the events of this trip was that it caused the rest of us to put together ditch bags that included portable communications, compass, GPS and flares. You never wish for a day like Jim had, but if it comes someday, we hope to be better prepared.

Then, one day the ocean turned on me, as it can happen with very little notice. That’s another story to be told. NS

Editor’s note: Jim Pex is an avid angler based out of Coos Bay and enjoys fishing for albacore, salmon and rockfish. He is retired and was previously CEO of International Forensic Experts LLC and a lieutenant with the Oregon State Police at its crime laboratory. Pex is the author of CSI: Moments from a Career in Forensic Science, available through Amazon.