Updated June 27, 2022, 12:15 p.m.

I’ve seen fire and passion while observing the Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission go about its business over the years, but never anything like this afternoon.

The subject? You guessed it – wolves.

There was distinctly different body language and audibly different tones in the voices of panel members and WDFW staffers as they spoke this afternoon about whether to adopt more binding rules around conflict prevention measures and lethal removals, the science around killing wolves, and how seriously the agency takes its role in managing the species’ recolonization and its impacts on cattle producers and others.

Things grew so emotional in Room 172 of the Natural Resource Building in Olympia that the state wolf policy manager felt attacked by a commissioner and a colleague stepped to the microphone to tell the member to direct their apparent ire at Director Kelly Susewind instead.

“Oh my goodness, it was awful,” said someone who witnessed today’s unsavory events personally and which are available on the TVW broadcast from roughly the 4:27:30 minute mark to 4:47:15.

It was the latest flashpoint as some of the Governor’s Office’s recent appointments thrash their way around the citizen panel that sets WDFW policy, with this particular discussion centered on essentially trumping what are regarded as hard-won protocols to prevent and deal with wolf-livestock conflicts, which cost the state of Washington a pretty penny in the form of an outside mediator who helped achieve agreement out of very disparate parties via the Wolf Advisory Group.

But it’s never been enough for some who want a sledgehammer instead of a rubber mallet and in September 2020 and hounded by hardcore wolf advocates, Governor Jay Inslee recommended the commission begin making new rules and policies around wolf-livestock conflicts.

After myriad meetings, that effort appears to have culminated today – in the military sense – with the commission essentially deciding instead to stick with what is working: protocols rather than binding rules that could have been challenged ad nauseam in court and thus tie up WDFW.

Those most in favor of shackling rules, Commissioners Lorna Smith of Port Townsend and Melanie Rowland of Twisp, simply did not have close to a majority to continue their line of pursuit and so had to abandon it.

Effectively, today’s nondecision decision marks a victory for WDFW and its management of the hot-button species.

The agency will take a lot of heat for acting too fast on wolves, acting too slow on wolves, but those who’ve been on the commission longer than Smith or Rowland appear comfortable with its approach.

Notably, that included Chair Barbara Baker of Olympia, who is, it can be argued, a predator advocate, but today saw her defending the status quo around predator management.

Recalling going to the Wolf Advisory Group before being appointed to the commission, Baker described what she recalled as a “combat zone” – “It was awful” – but then over time she saw stakeholders beginning to work together, thanks to mediator Francine Madden.

Producers may not be kissing wolves anytime soon, Baker acknowledged, but she added that passing a rule now would “chill the advancements we are making.”

Commissioner Kim Thorburn of Spokane said ranching communities would be harmed by the rule, and also lamented all the resources that still go into wolves, “which seem to be recovering fine,” when actually imperiled species need the attention far more.

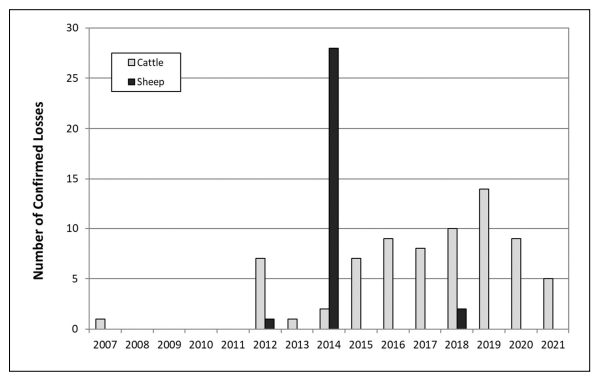

Vice Chair Molly Linville, a Douglas County cattle rancher long involved in the issue, pointed out that these days there are both fewer livestock depredations and wolf removals in Washington.

“Shame on us for not recognizing the win. We are winning. This makes me nuts,” Linville said.

Things got actually nuts soon afterward.

Commissioner Smith, who couched her support for rules as a need for set regulations versus the risk of losing staffers who shepherd an issue they’re committed to, said she wanted more information about everything leading up to a removal decision, using a thumb and forefinger to indicate not much is publicly posted on WDFW’s wolf update page.

That led Susewind to outline deep internal reviews of depredations and how and if there were attempts to head them off, with up to 20 staffers who take up to half a day in meetings before a regional team develops a recommendation that is forwarded to him for a decision, all of which produce reams of paperwork.

“There is thorough documentation; we have been to court many, many times,” Susewind said.

Three wolves were removed by WDFW last year, two so far this year, levels well below past years.

Commissioner Smith also said that based on science, lethally removing wolves isn’t a long- or medium-term solution.

Responded Julia Smith, WDFW wolf policy advisor, “There is a body of science that shows removals are effective.”

She added that, conversely, there is no science that range riding – a holy grail among wolf advocates – actually works, though WDFW believes it is important.

It all appeared to trigger Commissioner Rowland, a former federal ESA attorney, who asked to see her literature on the science of wolf removals.

Rowland also said she considered it “very serious” to kill wolves and stated her “personal position is, my personal belief, is that we are all doing it because we were all raised on the Big Bad Wolf theory and people don’t like wolves, they’re scared of them.”

That drew a very strong rebuttal from Susewind.

“We think it’s a big deal to kill wolves too, a very big deal,” the Director said. “Better or worse, there’s one person in the state that can authorize that and that’s me, and I take it as a very, very big deal. And it bothers me when people think I don’t. I’m sure not doing it because it’s the Big Bad Wolf. You said it, there’s one person who has that authority, that’s me, so I have to take that as aiming at me. I’m not afraid of the Big Bad Wolf. I put a lot of thought into these decisions.”

He said it wasn’t done for “the producer,” but rather “to implement a broader procedure.”

Removals are considered after set numbers of confirmed or probable attacks in rolling 30-day or 10-month windows, as it becomes clear wolves are becoming habituated to unnatural prey. By and large it all works.

After Rowland protested that she wasn’t saying Susewind didn’t believe it a big deal and Susewind said it feels like commissioners were attacking his staff, Julia Smith’s reaction to Rowland’s comments – she left the room – drew attention.

Just off TVW’s camera, WDFW Deputy Director Amy Windrope addressed it.

“Our staff gives their soul to this work and you may disagree with the outcome of that work, but it’s pretty hard to sit here and feel like you’re alone.” Windrope said. “And I think it’s better to direct your ire at Director Susewind. That’s just where it belongs.”

Rowland said she hadn’t been attacking Julia Smith about the science. “I was asking for the basic information that this is accomplishing what it is meant to accomplish,” she said. “That has nothing to do with a personal attack on Julia.”

“I’m just telling you how it was received,” Windrope responded.

Some commissioners have, in fact, been questioning if not poo-pooing WDFW staffers’ science and data, and not just on wolves but black bears and other species.

Julia Smith spoke again shortly afterwards and stated that she was both a wolf and wildlife advocate who takes wolf management seriously, an “issue near and dear to my heart.”

She described receiving two calls recently, from Arizona Game and Fish and Colorado, both on wolves, and asked rhetorically why had they reached out to her. Because, she said, Washington has a better track record than any other state.

“What are you doing there that is working?” they wanted to know, Julia Smith said.

This spring Conservation Northwest found that from 2017 through 2021 Washington wolves had the lowest rate of human-caused mortality out of the five Northwest states where the species is either fully or partially federally delisted and called the state “the best place to live if you are a wolf in the western United States.”

It was an all but unstated rebuke of those who routinely portray WDFW wolf management as seriously inadequate and say the agency is “bought and paid for by special interests.”

Julia Smith said Washington spends more on nonlethal measures than other states and that “a ton” more is spent on nonlethal work than lethal. She also acknowledged that wolf depredations and removals would “never get to zero,” a “reality of having wolves and livestock on the landscape.”

During a break in the meeting afterwards, an observer said Windrope spoke to Rowland about how “inappropriate and hurtful” her comments had been to Smith, but “Rowland thinks that she did nothing wrong and that Julia was just overly sensitive.”

“If they keep this up, no one but anti-hunters will be willing to work for the department,” the observer said, stating that Dr. Stephanie Simek, WDFW’s lead on the spring bear hunt and who had deeply defended it, had been “lost.”

That Simek may have left WDFW could not immediately be confirmed – her email is still listed in the agency’s employee contact list, a test email didn’t bounce back and multiple spokespersons were not picking up calls late Friday night. On Saturday one said they “can’t comment on personnel matters.”

It may or may not have been notable that the commission’s spring bear policy discussion later in the day’s meeting was led by Wildlife Program Director Eric Gardner and Game Division Manager Anis Aoude rather than Simek, who gave the past presentations. Gardner stated that for upcoming discussions around the topic “we won’t have Stephanie.”

Back in Friday’s meeting, as things calmed down, Chair Baker observed that Governor Inslee’s recommendation to the commission to pass a wolf rule was “a little under the gun.”

And then the commission took up the equally thorny issue of a spring bear policy, and tomorrow will hold a public hearing on increasing cougar tags in the Blue Mountains to reduce lion predation on a struggling elk herd.

The fun never ends these days. And that is all the time I have for this.