Feds Announce Gray Wolf Lower 48 Delisting, Including Western Two-thirds Of WA, OR

Editor’s note: Updated 7:55 a.m., October 30, 2020, with comments from a spokesman for Oregon Governor Kate Brown in the 17th paragraph.

Northwest hunters and others are hailing today’s announcement that gray wolves will finally be federally delisted in the Lower 48, fully moving the species’ management in the western two-thirds to the states of Washington and Oregon.

“After more than 45 years as a listed species, the gray wolf has exceeded all conservation goals for recovery. Today’s announcement simply reflects the determination that this species is neither a threatened nor endangered species based on the specific factors Congress has laid out in the law,” said Secretary of the Interior David L. Bernhardt at a Minnesota national wildlife refuge today.

US Fish and Wildlife Service Director Aurelia Skipwith called it “a win for the gray wolf and the American people. I am grateful for these partnerships with States and Tribes and their commitment to sustainable management of wolves that will ensure the species long-term survival following this delisting.”

Wolves in the eastern third of Washington and Oregon, along with Idaho and Montana, were Congressionally delisted in the early 2010s and are managed by state and tribal wildlife agencies in their respective jurisdictions.

Last year USFWS announced it would again begin considering the question of gray wolf recovery below the rest of the Canadian border. Thursday’s announcement comes five days before the presidential election.

While environmental groups denounced the delisting, the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation applauded it, saying that populations are the “highest they have ever been in both Oregon and Washington.”

“RMEF firmly supports the removal of federal protections for wolves so they can be appropriately managed by state wildlife agencies through regulated hunting and trapping,” said Kyle Weaver, RMEF president and CEO.

The latest annual reports from ODFW and WDFW say there were a minimum – meaning at the very least and likely many more – of 158 wolves in Oregon at the end of 2019 and 145 in Washington.

Washington U.S. Rep. Dan Newhouse, a Yakima Valley Republican, said that by moving full management of wolves to the states, “the federal government is recognizing the effectiveness of locally-led conservation efforts, basing management decisions on sound science – instead of politics, and providing certainty to families, farmers, and rural communities in Central Washington and throughout the country.”

For its part, WDFW pointed to a 2019 letter from Director Kelly Susewind to the feds in support of federally delisting all of Washington.

“WDFW supports and facilitates the recovery of wolves in Washington and feel that delisting is appropriate considering the rate of recovery. This move won’t change how we manage wolves in this state and our priorities remain the same; focusing on continued recovery and reducing conflict between wolves and livestock,” said spokeswoman Staci Lehman.

Hunter’s Heritage Council President Mark Pidgeon said the federal action was “heaven sent” for his state, Washington.

“With a rapidly expanding wolf population, and two-thirds of the state of Washington being federally protected, moose and elk herds are in serious decline. Washington sportsmen strongly support the return of state management authority over wolves,” he said.

Gray wolf impacts on Evergreen State ungulates are the subject of ongoing research in two key hunting areas, the Okanogan and northeast corner. WDFW says there’s “no evidence” wolves are affecting big game populations, but transborder woodland caribou have been extirpated from the southern Selkirk Range in part due to wolf as well as cougar predation.

“Oregon sportsmen and women applaud the Department of the Interior delisting of the gray wolf. Their recovery is a conservation success story and the delisting should be celebrated. We look forward to our renowned state agencies and local biologists taking over wolf management,” said Oregon Outdoor Council President Dominic Aiello.

ODFW referred a reporter to Governor Kate Brown’s office after last year she undercut the state agency’s director, Curt Melcher, who had supported the proposed delisting.

“In Oregon, we have a wolf recovery plan that is based on science,” said Charles Boyle, a spokesman for Gov. Brown. “That plan is working well, compensating ranchers who lose animals while helping to restore the full biodiversity of Oregon and bring back a wolf population that was brought to the brink of extinction by the management policies of the last century. The development of Oregon’s wolf recovery plan involved many hours of public participation so we could painstakingly balance stakeholder needs. A significant part of that plan relies on federal protection across Western states. The science for wolf population management in the U.S. has not changed. The timing of these proposed changes to federal wolf protections is suspect, and needlessly politicizes this issue. Our wolf recovery plan is working in Oregon—we don’t need the federal administration to fix something that isn’t broken.”

Environmental groups vowed to fire off a legal challenge, claiming that the Endangered Species Act “demands more, including restoring the species in the ample suitable habitats afforded by the wild public lands throughout the West.”

Nick Cady of Cascadia Wildlands in Eugene considered it a political stunt and called wolves “the latest victim of Trump’s desperate reelection bid.”

According to USFWS, ESA does not require wolves occupy all former habitats, rather measures “whether wolves are in danger of extinction (endangered) or at risk of becoming so in the foreseeable future (threatened) throughout all or a significant portion of its range. By any scientific measure, gray wolves no longer meet the ESA’s standard for protection and so should be delisted.”

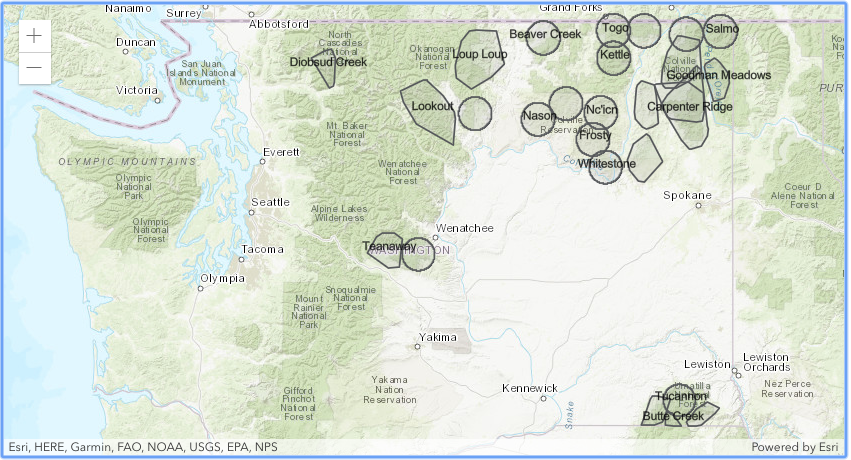

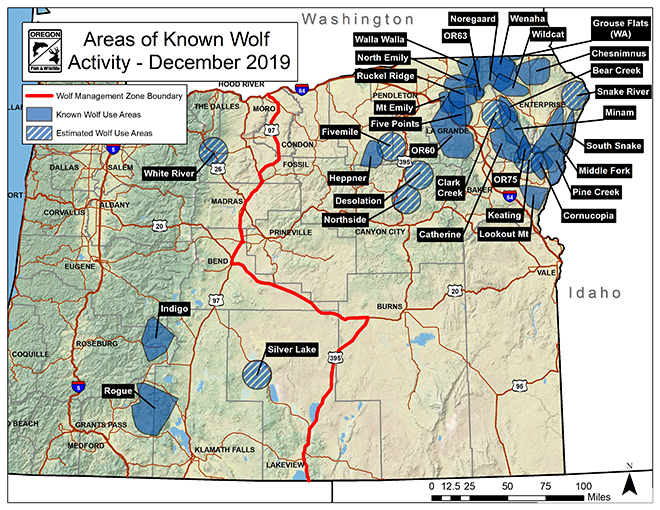

Wolves have spread from the initial two packs in Northcentral Washington and Northeast Oregon in 2008 to throughout Northeast and Southeast Washington’s mountains and the east-central Cascades of that state, as well the northern and southern Cascades of Oregon.

There are reports of a new pack at the southern end of Washington’s Sawtooth Range and another that dens on the British Columbia side of the Pasayten Wilderness but forays south of the international border. Earlier this week, a member of a California pack turned up in Oregon, likely where the Golden State’s wolves originated and illustrative of connectivity between populations.

The recovery of wolves in the Northwest follows a long period of persecution and began in the late 1980s as packs moved into Northwest Montana and then was turbocharged with the release of dozens into Central Idaho’s wilderness and Yellowstone National Park.

Today there are an estimated 1,900 wolves on the West Coast and Northern Rockies and 4,200 in the Great Lakes, with as many as 15,000 in Canada north of the Northwestern U.S.

The species has proven to be highly adaptable as well as controversial. Today’s announcement will do nothing to diminish either characteristic.

From a nuts and bolts standpoint, USFWS will make the delisting official with a Nov. 3 rule posted on the Federal Register and which will become effective 60 days later, or Jan. 4, 2021. That is when WDFW, ODFW and tribes in the western two-thirds of Washington and Oregon would take over full management.

Even so, USFWS says it will “continue monitoring gray wolves for five years to ensure continued success.”

As for hunting wolves, while two different tribes have hunted them on and off their Northeast Washington reservations for years, it may be some time before state hunts are allowed. WDFW has begun post-recovery planning and would need to change the state listing and game status of wolves.