Beavers Are Vital, But Is It Necessary To Ban Trapping Them In The Siuslaw NF?

You will find few more fervent beaver believers in the Northwest than yours truly.

I’ve been to the muddy lodge and seen the light, brothers and sisters!

I’m here to preach that our furry, flat-tailed, bucktoothed aquatic engineers are dam good for fish, healthy streams, riparian areas, wildlife habitat, flood control, and more critical environmental and ecosystem functions, can I get an amen?!

As I wrote a few years back:

“… Mother Nature’s chainjawed little logger may be part of the solution to our salmon and steelhead woes.

While we fill out paperwork, he fells trees.

While we fester over designs, he dams.

While we hold public meetings, he holds back water.

While we put plans out for review, he creates fish habitat.

While we scrounge under couch cushions for project funding, he’s working off the clock, 24/7/365.

And when we finally get around to Doing Something, he’s back in his lodge, popping a cold one and binge-watching Leave It To Beaver.

–Me, March 10, 2017

Who can do it?!? Castor canadensis can!!

So you’d think that I’d have pushed my wood chips all in in support of an effort to ban beaver trapping in Western Oregon’s Siuslaw National Forest.

Timb – er, not so fast.

What I like best is when wildlife management decisions are guided by science and facts, not fanned by wishful thinking nor part of backdoor end-arounds.

Given the low number of beavers trapped in Oregon in recent years, the very low value of their pelts and the stable population, there doesn’t appear to be a conservation concern in this rainy range that warrants a blanket trapping ban.

What’s more, national forest management might need to dramatically change to result in larger beaver numbers and accrue more benefits for fish, wildlife and streams.

Right now riparian corridors here are protected from logging — a very, very good thing compared to past practices where trees were toppled right down to the banks, and logs were also yarded out of the water in the mistaken belief it would help fish migration.

While those days are behind us, trees will still be trees.

When Doug firs, cedars, spruces and hemlocks are protected, watered voluminously, given a little sunlight and allowed to grow, they tend to shade out the kinds of trees and shrubs that beavers like best.

Meaning that for the foreseeable decades before the Siuslaw becomes more old growthlike and reopens, allowing the understory to rebound, there will be less and less building materials available for their dams, fewer and fewer stems to snack on back in the stickhouse.

That makes this trapping ban proposal a feel-good measure and, frankly, more about the piecemeal chiseling away of the activity than something that would yield quantifiable real-world benefits.

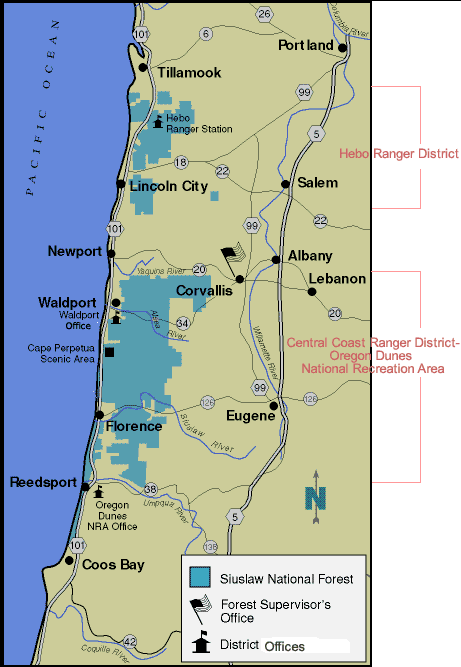

THE REASON I BRING THIS UP is because the Oregon Fish and Wildlife Commission will set the 2020-22 furbearer regulations late next week, and they’re being pressured to close beaver trapping on the Siuslaw NF, while others want it banned on all federal lands in the state.

In dozens of public comments submitted to the citizen panel, they point to the aforementioned benefits of beavers.

Critter habitat, expanded wetlands, groundwater storage, carbon sequestration, slower storm runoff, wildfire breaks and wildlife viewing are some of the positives listed in a typical public comment like the one from Suzie Savoie of the Applegate Valley.

And then there are are those like Kelly McAllister who considers trapping to be “barbaric, indiscriminate and unnecessarily cruel. This is not the 1800s.”

Curiously, the fur-trapping days of that century actually seem to have passed over the Coast Range, “primarily due to the difficulty of traversing that landscape and native tribes were not accustomed to hunting and trading beaver pelts,” according to an ODFW report prepared for the commission on the matter.

Agency staffers aren’t recommending any change to coming years’ beaver trapping rules.

While they’re willing to work with the federal foresters, they state that “no data nor scientific findings have identified any areas warranting a harvest closure. In fact, all Department and external data indicates limited harvest and impact, intact, connected populations with wide distribution, and widespread beaver habitat limitations.”

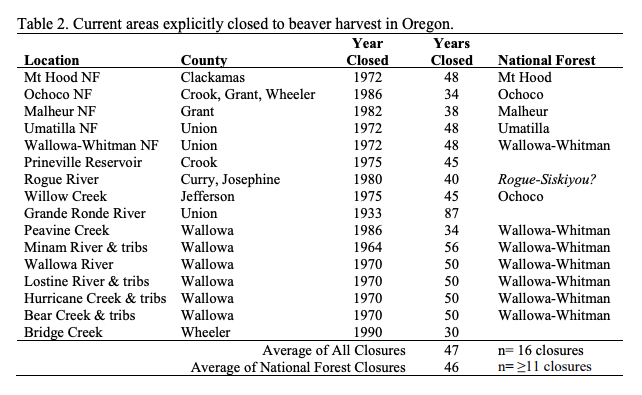

Oregon does in fact have some areas where beavers can’t be trapped, and most have been around a very long time – 47 years on average. They’re mostly on national forests, primarily east of the Cascades.

Those were implemented “in concert with beaver relocation efforts but many of those were reported to have failed because beaver left the release site due to poor habitat conditions,” according to ODFW staff.

In comments opposing the ban, Charles Carnahan of Coquille detailed how as a young man in the mid-1970s, trapping in the “high coast range” helped him pay for his degree in wildlife management from Oregon State University in Corvallis, just east of the Siuslaw.

But changing forest practices have led to an overstory that shaded out the alders and brush that are “absolutely necessary for any viable beaver habitat,” he states.

“Over the years of my trapping career I witnessed a drastic drop in beaver colonies in the high coast range due to habitat loss, not trapping [emphasis his],” Carnahan notes.

Current low fur prices and the labor-intensive nature of stretching pelts essentially make a ban redundant.

“When I started trapping, one beaver equaled two days wages at minimum wage, today it takes close to ten beaver to equal one days wage at minimum wage. It does not make economic sense to pursue beaver in the high country at this time,” Carnahan writes.

He says to enhance their populations in the Siuslaw National Forest, “extreme measures” should be taken in regards to their habitat instead.

According to ODFW, 2017’s trapper-reported statewide beaver take of 981 was the “lowest since harvest was re-opened in 1951,”

The longterm reduction is linked to “a decline in furtakers and effort … a likely by-product of relatively poor pelt prices” rather than dropping beaver numbers.

These days, given better habitat in the lowlands and industrial timberlands, that’s where the large rodents primarily live– and cause issues for property owners who may not want or need any freelance irrigation of their back 40 or stand of timber.

“Many beaver from the relatively low annual harvest are taken in response to resolving damage complaints on private land,” the ODFW report states.

Average take in the two core counties of the Siuslaw National Forest for 2014 through 2018 was 154 in Tillamook, 20 in Lincoln.

HOW BEAVERS BENEFIT SALMON is well recognized, and ODFW notes that in 1997 it requested trappers to voluntarily not work coho streams – strongly associated with beaver habitat – on the coast.

Follow-up phone surveys a couple years later determined that just 1.2 percent of the beaver harvest occurred in those waters, and that across Western Oregon it declined from 4,239 to 2,612.

That could also be a function of pelt prices over those years, which have varied from as much as $21 in 2005 ($28 today adjusted for inflation) to a paltry $8 in 2019.

“I am particularly concerned by this petition,” wrote longtime trapper Tom Nygren of Hillsboro in comments to the Fish and Wildlife Commission, “because I see it as a ploy to ban trapping in general, since there is no real evidence that a closure on beaver trapping will have any demonstrated scientifically based benefit on the watershed given the limited and distributed trapping activity that occurs today.”

ODFW says it has received “no empirical connection between a requested ban and desired goals” from the Siuslaw National Forest.

And when it asked for information from the five forests that the proposal was based on, “either limited or no data was available to provide any insight on if these closures actually benefited beaver or improved fish habitat.”

The info that was on hand suggested beaver abundance was actually higher where they were trapped. Agency staffers say beavers can sustain 30 percent harvest annually.

Besides a lack of habitat that is constraining beaver numbers, there’s another key factor to consider.

“Beaver simply cannot survive cougar predation in the small coastal tributaries, especially in the low water conditions of summer,” wrote Wayne Loyd of Drain in comments opposed the trapping ban.

Other predators include bobcats, coyotes and bears that pick them off around their ponds and as young ones disperse to new waters.

IRONICALLY, WHEN I LEARNED about this proposal to ban trapping in the Siuslaw National Forest, as a beaver booster – “rodent beyond compare!” I cheered a few years ago – my initial thought was that it might be a good idea and that the opposition’s reaction was way over the top.

With the insanely cost-effective benefits beavers provide, you could literally not engineer a better natural engineer, a critical job as we work to restore salmon and steelhead runs and riparian areas.

Who’s not on board with a feedback loop that begets more fish to catch?!?

But taking a deeper look, this particular instance boils down to a social question, not a conservation need.

I can get behind legitimate conservation needs, but this feels like it’s an effort to end a legitimate use of a natural resource and sideline the people with the deepest connections to it.

I don’t know about you, but good grief, that one-sided, winner-take-all approach isn’t the way forward anymore.

Even if federal biologists are drawing up plans that would allow streamside forests throughout the Siuslaw to be opened up to create more dam-building material and forage – “increasing large wood loading, beaver habitat, and wetland/offchannel connectivity, and … increasing native riparian vegetation to provide bank stability and shade stream reaches during warm summer months,” are part of NMFS’s Oregon Coast coho recovery plan – low market demand for beaver fur will continue to be a disincentive for trappers. If pelt prices do rise, a rising beaver population could handle harvest. And ODFW’s request to not work coho waters would still be in place.

Win, win, win, win, win.

Meanwhile, agency staff are recommending that trapping season continue as in the past, open from Nov. 15 through March 15 outside of those longterm closures.