An Interesting Week At North Of Falcon

These have been active days in the Western Washington salmon fishing world.

As North of Falcon negotiations on 2021-22 Chinook, coho, pink, sockeye and chum seasons enter the final two weeks and WDFW managers outlined their Pugetropolis proposals on Wednesday, a sharp rift has emerged in the sportfishing community this week.

A North Sound organization frustrated with the agency’s results in recent years is preparing to head to U.S. District Court over the federal fishery authorization process, and that has one angling leader warning of potentially dire consequences to state opportunities.

At the same time, WDFW and tribal fishing managers preached cooperation and comanagement in a Seattle Times op-ed earlier this week, and yesterday they reinforced that message in an hour-and-a-half-long live broadcast that also shared the recovery challenges and work being done on the Stillaguamish system for its Chinook, a key fisheries-constraining stock.

It’s a whole lot to chew on, so I’ll try to take them one by one.

CLAIMING “ONGOING VIOLATIONS OF THE Endangered Species Act and related court orders and management plans,” Brett Rosson of Fish Northwest of Anacortes says the organization will file as early as this coming Monday, April 5, for “preliminary and permanent injunctive relief” against federal and state agencies over the use of ESA Section 7 consultations in greenlighting salmon seasons.

Fish Northwest bills itself as “dedicated to giving Puget Sound recreational fisherman a voice through legal and legislative action.”

Rosson et al are particularly frustrated with this past winter’s closure of blackmouth fisheries in the San Juans and North Sound waters, ongoing state-tribal Chinook and coho catch disparities in favor of the latter fleet, and the structure of NOF that now piggybacks WDFW’s salmon permit on the tribe’s application to the feds, weakening the state’s position, they feel.

Last fall they filed a motion to intervene in the Boldt Decision. The state, feds and tribes – the parties in the long-running case – all asked a judge to decline the motion. At last check, no decision had been made.

But it’s their new threatened lawsuit that has Ron Garner, Puget Sound Anglers state board president, circulating a warning to his organization’s chapters about potential “unintended consequences.”

“Are we ready to roll the dice on shutting down our fishing with the possibility of it not reopening for years, or possibly forever? This lawsuit could do that. This has to be said,” states Garner.

With contacts at the federal and state levels and in tribal communities, Garner worries the lawsuit could be “the push” that leads the tribes to jettison the state from the jointly applied fisheries permit that, through Section 7 consultations, is fast-tracked for review.

He says he’s been told a go-it-alone state permit would take two years to process, and afterwards it would likely be challenged in court by wild salmon advocates.

“Be careful what you wish for and really think these issues out,” Garner urged PSA’s chapters. “If you are struggling now with the small fishing seasons, if played out wrong, we will be lucky to even get what we have now as the new normal. I have made calls to people that are higher up and none of them are optimistic that this case is a win. Most think it will turn us backward. None have said it is a winning case. This case, if heard, will cost millions of dollars, not hundreds of thousands.”

It’s far from Garner’s only iron in the salmon fire; he has also been working to tweak a WDFW hatchery policy governing production oversight.

But in a point by point response, Fish Northwest’s Rosson says Garner is fear mongering and that WDFW should have long ago sought its own fisheries permit to level the playing field with the tribes when it comes to divvying up the fish.

Rosson has acknowledged that the lawsuit could potentially hold up the summer salmon season, characterizing that as “one of the possible outcomes but certainly not an expected outcome. As our lawsuit describes, NMFS is in violation of its use of Section 7, and a judge will decide if that’s true.”

A LEARNED OBSERVER WHO I CONSULTED told me that while they understand where Fish Northwest is coming from, the organization also faces an “uphill climb” in acquiring an injunction that would affect this year’s salmon seasons.

They say Fish Northwest would need to convince the judge 1) that they would likely succeed on their claim’s merits – “which might be no small task” – 2 and 3) show evidence of irreparable harm and that their injunction would be in the public interest, along with 4) establish how the “balance of equities” are in the organization’s favor.

Given the thrust of what’s been made public about the lawsuit – that the process is somehow flawed – those last two tasks “present a very high bar to overcome, and particularly so because tribal treaty-guaranteed rights are involved,” the observer says.

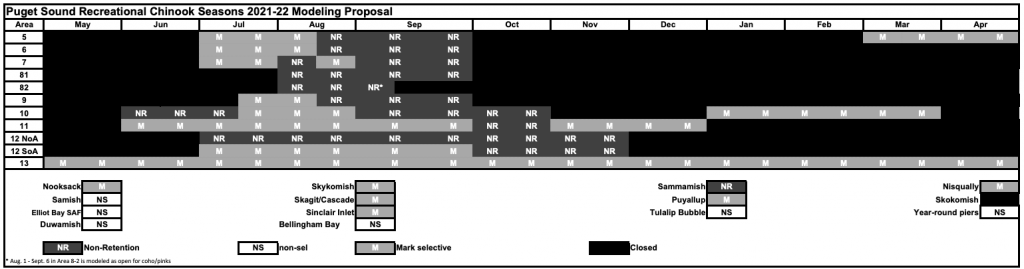

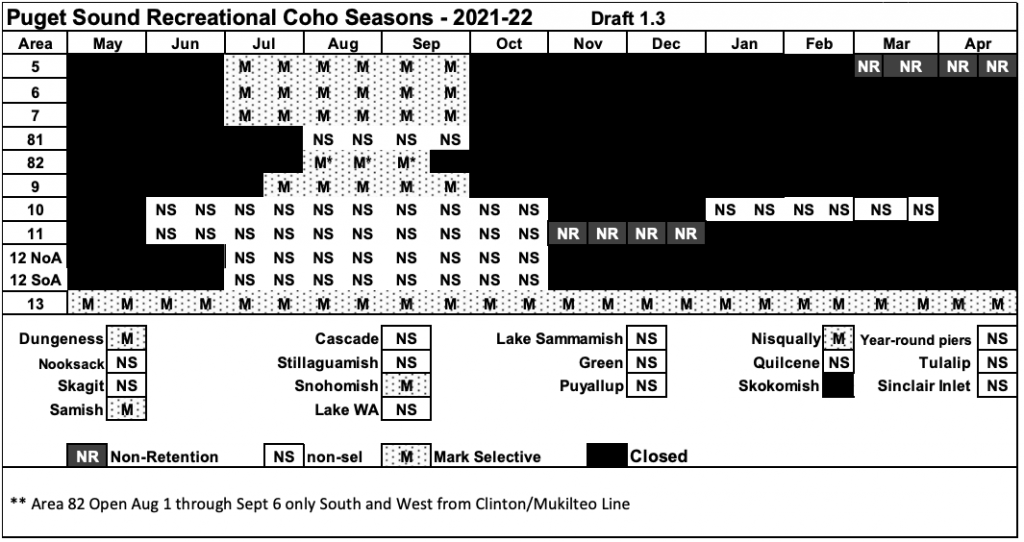

AS FOR THOSE PROPOSED STATE SALMON SEASONS, WDFW unveiled an initial set for public comment yesterday.

They’re highlighted by bonus bags on pink salmon in some rivers – up to six in the Duwamish/Green and Puyallup/Carbon, four in the Skagit – but not in the salt to protect some weaker coho runs that come in around the same time.

Only a small portion of Area 8-2 would be open for hatchery silvers, and it would be completely closed during the peak of the run back to the Snohomish, another blow to a longtime local derby and one in a series since The Blob but also protective of a key wild stock struggling in recent years. Wild coho retention would also be off limits in the Straits and San Juans throughout the season.

While Baker Lake was initially proposed as “closed to salmon fishing,” WDFW now appears to be amenable to a “TBD” placeholder in the final agreement with the tribes, just in case the run comes in larger than the preseason forecast.

On the Chinook side, North Fork Nooksack and lower Skagit springer fisheries are on the docket, along with a long weekend on Elliott Bay plus non-selective fall king fishing in the DGR, but no North Sound blackmouth at this point and still no fall Skokomish opener due to the boundary dispute with the local tribe.

You can provide feedback to WDFW here.

YET WHILE THERE ARE MANY DISPUTES between the state and tribes – and not just this time of year and not just on fisheries – Wednesday afternoon saw WDFW and Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission leaders talk about collaboration in shaping salmon fisheries and conserving and recovering runs.

“We are better together,” emphasized Kelly Susewind, the WDFW director.

He was speaking during what has become an annual “plenary session” – a gathering of all the participants – held as North of Falcon nears crunch time and which also came after urging from some sport anglers to make the process more transparent. Up to 111 tuned in via Zoom, which another couple dozen watching the TVW feed on WDFW’s Facebook page, according to agency spokeswoman Carrie McCausland.

While Susewind may not have been directly addressing Fish Northwest, he did encourage constituents “not to foster divisiveness. This is about sticking together.”

It was the same with Lorraine Loomis, NWIFC chair, who quoted longtime organization head Billy Frank Jr. to say that if the parties resort to litigation to solve their differences, “we’ll all lose,” the salmon included.

Comanagement of salmon and steelhead, of course, came out of litigation, 1974’s aforementioned Boldt Decision which followed a long history of Washington state actively suppressing treaty-guaranteed harvest rights.

After WDFW’s Ron Warren and NWIFC’s Craig Bowhay gave high-level outlines of internal state and tribal NOF processes, the discussion turned to the Stillaguamish River and its Chinook, in a sense coming full circle to the lawsuits.

A constraining stock due to perpetually low runs and poor basin productivity, Washington salmon fisheries impacting them are managed to an overall 12 percent mortality rate. After Alaska and British Columbia fisheries take the lion’s share, this season that amounts to 64 dead fish. And so earlier on Wednesday, WDFW staffers shared a complex model with anglers that factored in how many Stilly kings were saved or eaten up in Puget Sound under various proposed fishing scenarios.

Delay the start of a season here and shave off of 2/10ths of a fish; but add time over there and impacts can get very expensive, very fast.

If that stringent protection of a stock has deeply frustrated state anglers like Fish Northwest for its big impact on San Juans blackmouth fisheries, Shawn Yanity, chair of the Stillaguamish Tribe, which is trying to recover it, allowed that in the past Lummi and Muckleshoot fishermen may not have been too pleased with him either, a rare glance at intertribal frictions.

Yanity said that while his tribe had a cumulative quota of 355 Chinook from 2011 through 2020, they only harvested 53 over that time. He said the rest have been blessed to go upstream and spawn – but he also expressed alarm at the amount of illegal fishing gear in salmon holes and snag marks observed on those same fish. The Stilly is not open for Chinook retention.

Asked by Puget Sound charterboat skipper Carl Nyman if any plans were in the works to increase capacity at the Stillaguamish’s Chinook hatchery, which produces up to 200,000 natural-origin fish, Yanity said he hears the question often, but pointed out that no matter how many fish the tribe raises, there also still must be habitat for them to rear.

There is also pinniped predation to contend with.

Yanity also expressed hesitance about tipping “the scales too much” with further human alterations to the stock, but he did add that if the kings continue to decline despite the conservation facility, next steps are also being considered among the comanagers, which may bring federal overseers into the conversation and that the public might need to help push on them.

Essentially, to ever be able to ease wider Puget Sound salmon fishing constraints, much more of the river system’s habitats need to be reclaimed and become more productive for more young Chinook, especially the estuaries, critical rearing space, and that was the subject of an early 2020 film, Lifeblood, that featured the partnership of Yanity, PSA’s Ron Garner and WDFW towards that end.

“Ask not what the Stilly can do for you. Ask what you can do for the Stilly,” Jeff Davis, the agency’s conservation director, told plenary session attendees. “Salmon recovery and restoration, they’re not just about getting our opportunities back in our lifetime; they’re about the future generations and I think we all want our folks learning how to fish, landing their first fish and teaching their kids and grandkids all about fishing and the importance of salmon to our overall health.”

One of the last people to speak during the session was far removed from the basin, Ilwaco-based guide Butch Smith, but he echoed the afternoon’s theme.

“We are in this together; the stronger the partnership, the better the whole,” Smith said.

That may be tested early next week and afterwards.

Correction, 11:10 a.m., April 1, 2021: The spelling of the first name of Shawn Yanity, Stillaguamish Tribe chairman, was initially misspelled and has since been corrected. I regret the error.