Support For Lake Washington Sockeye Restoration Assessment At Meeting

With a show of hands last night in Renton, anglers and others asked a longtime Lake Washington sockeye advocate to request WDFW look into what it would take to recover the salmon stock and restore the fabled metro fishery.

It’s a long-shot proposition with seemingly all factors now lined up against the fish, and two of the people who’d gathered in the Red Lion conference room supported just throwing in the towel instead.

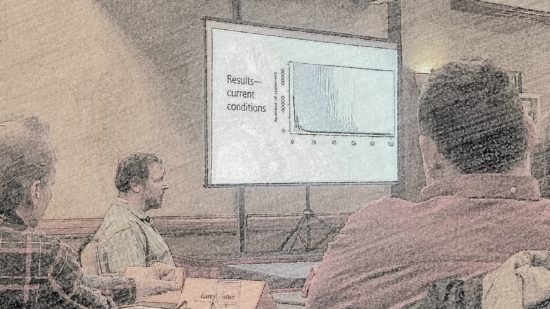

But nobody was in favor of the status quo, which is modeled to lead to the extinction of the run in 40 years time — perhaps as few as 30 with this year’s lowest-ever forecast of just 15,153 back to the Ballard Locks is any indication, according to the local state fisheries biologist.

“The reality is, it’s going to be very, very, very tough to get all the players to do something,” acknowledged Frank Urabeck before calling for the vote from the 40 or so members of the public and 10 members of the Cedar River Council.

Not everyone held up a hand for any option, but Urabeck’s plan is to approach WDFW Director Kelly Susewind and ask that the agency conduct a feasibility assessment on what can be done and how much it would cost to bring sockeye back to fishable numbers.

Urabeck said it would likely require “a massive effort, a huge amount of money.”

But even as predation on smolts in the lake grows and more and more adult sockeye are dying between the Ballard Locks and the Cedar River, there are still some glimmers of hope.

The meeting followed on a similar one last year but which did not include Seattle Public Utilities.

Last night, SPU was at the table in the form of watershed manager Amy LaBarge, who gave a presentation about the utility’s Landsburg mitigation hatchery, completed in 2012 with a capacity of 34 million sockeye eggs, but which has only ever been able to collect 18 million due to low returns.

And since that 2018 gathering, Urabeck indicated that there had been talks going on behind the scenes too.

“I can’t say if I’m optimistic, but there has been dialogue,” he said near the end of the two-hour meeting.

Other players in the issue include the Muckleshoot Tribe and WDFW, the latter of which operates the sockeye hatchery for SPU.

Brody Antipa, the regional hatchery manager for the state agency, was in house and he talked about how he began his career as the guy who “lived in a trailer down by the river” at the old temporary facility on the Cedar, which was opened in the early 1990s over concerns that the run at the time was faltering.

The system produced reliably high returns of as many as 400,000 spawners into the river in the 1960s and 1970s, at the end of the era when Lake Washington was thick with blue-green algae that hid the smolts from predators.

Following cleanup efforts, water clarity went from as little as 30 inches in 1964 to 10 feet in 1968 to up to 25 feet in 1990, according to WDFW district fisheries biologist Aaron Bosworth.

Native cutthroat and northern pikeminnow primarily but also nonnative bass, yellow perch and other species suddenly had the advantage over the young sockeye.

The years of 400,000 reds on the redds were over just as anglers had figured out how to reliably catch sockeye in the lake with just a plain old red hook.

In the 1990s, Antipa said that testing at the hatchery determined that feeding the young sockeye was helpful before turning them loose to rear in the lake a year to 14 months.

By the early 2000s, fisheries went from once every four years to once every other year — 2002, 2004, 2006.

But since then there’s been nothing but a string of increasingly bad years, with last fall seeing just 7,476 of the 32,103 sockeye that went through the locks reaching the Cedar, despite no directed fisheries and only a small biological sampling program operating at Ballard.

The rest died from prespawn mortality caused by fish diseases that may have become more deadly and prevalent due to warmer water in the Lake Washington Ship Canal.

During last night’s question-and-answer period, the audience and Cedar River Council members focused on tweaking the hatchery operations — whether or not Baker and Fraser sockeye could be used to reach full eggtake capacity; if the facility was able to hold the fry longer for a feeding and later-release programs that show promise; and if it could be used to just raise coho and Chinook instead.

The short-term answer to all that was “no” — the current management plan that the hatchery operates under doesn’t allow it.

So, asked a member of the council, how do we change that plan?

LaBarge, the SPU staffer, said that would need to go through stakeholders to get buy-in.

“The conversation is starting about that,” she said.

Another issue is all the predators in Lake Washington.

Antipa said that where once just getting 40 million fry into the lake all but guaranteed a fishery a few years later, the 70 million that swam out of the Cedar in 2012 didn’t result in anything.

Partly that’s due to the circular feedback of PSM issues affecting how many eggs are available at the hatchery and in the gravel , but rock bass have joined the suite of piscovores, along with walleye and at least one northern pike.

A bill on its way to Gov. Inslee’s desk would require WDFW to drop daily and size limits on largemouth and smallmouth in Lake Washington, along with all other waters used by sea-going salmonids in the state.

Realistically that won’t do diddly to bass populations, but gillnetting efforts the Muckleshoots have begun more seriously next door in Lake Sammamish might.

Before the show of hands, Max Prinsen, the chair of the Cedar River Council, recalled how in 1979 he came north from California at a time when bald eagles and condors were “gone” in the Golden State.

“But with changes we made as a society we brought those species back,” he noted.

After Urabeck’s vote, he spoke again.

“These fish aren’t just important as a fishery, but as a part of Northwest life,” Prinsen said. “I think it’s important to conserve this resource. It’s great to see this much interest.”

I would quibble with his use of the word “resource” — by chance this morning on the bus while proofing our Alaska magazine I read a quote from the author Amy Gulick about a Tlingit woman in Sitka who taught her that “The word ‘resource’ implies an end product, a commodity. But ‘relationship’ is so much deeper and multi-faceted. If you have a relationship with salmon, then you also have a relationship to a river, a home stream and the ocean. And you probably have relationships with people in your community connected to each other by way of salmon. We show gratitude for healthy relationships because they make our lives richer.”

But Prinsen was also among those who’d raised their hands, and I’ll bet something along the lines of a relationship with the sockeye was what he meant anyway.