Stopping Salmon Fishing Won’t Save Puget Sound’s Orcas

The idea that we can save Puget Sound’s starving orcas by just stopping salmon fishing for a few years once again reared its misinformed head, this time in a big-city newspaper piece.

In a black-or-white summary of a very complex problem, the nut was that we humans were shamefully avoiding looking at our own consumption of the iconic marine mammal’s primary feedstock.

Leaving that aspect out of the state of Washington’s recovery plan meant that, “We have decided, collectively though passively, to let the Puget Sound orcas go extinct,” it lamented.

We haven’t really, but nonetheless the prominence of the piece left leaders of the region’s angling community disappointed, as well as worried that it could lead to “knee-jerk” responses as Washington responds to the crisis.

And one has also asked the author to take another look at the issue with more informed sources to balance out the very biased one it primarily quoted.

THE ARTICLE IN QUESTION WAS a column by Danny Westneat in the Seattle Times last weekend in which he quoted Kurt Beardslee at the Wild Fish Conservancy.

“To cut back on fishing is an absolute no brainer, as a way to immediately boost food available for killer whale,” Beardslee told Westneat. “But harvest reductions are essentially not in the governor’s task force recommendations. We have a patient that is starving to death, and we’re ignoring the one thing that could help feed the patient right now. We’re flat out choosing not to do it.”

Columns are columns, meaning they’re not necessarily like a he said-she said straight news story, but what wasn’t mentioned at all was Beardslee’s complicity in the orca crisis.

So I’m going to try to shed a little more light on that and other things here.

AS IT TURNS OUT, WE HAVE BEEN cutting back on Chinook fishing.

Have been for years.

Ninety percent — 9-0 — alone in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, Puget Sound and the San Juan Islands, key foraging areas for the southern residents, over the past 25 years.

And yet so far J, K and L Pods appear to have shown no response.

In fact, they have unfortunately declined from nearly 100 members in the mid-1990s to 74 as of late 2018.

All while West Coast and Salish Chinook available to them actually saw nominal increases as a whole, according to state and federal estimates.

So I’m not sure what Beardlee expects to magically happen when he tells Westneat, “It’s easy to see how cutting the fisheries’ take in half, or eliminating it entirely on a short-term emergency basis, could provide a big boost.”

I mean, how is the 10 percent sliver that’s left going to help if the closure of the other 90 percent coincided with the cumulative loss of 25 percent of the orca population over the same period?

Don’t get me wrong, fishermen want to help too. Some of the most poignant stories I’ve heard in all this are angler-orca interactions.

But it’s not as cut-and-dried as not harvesting the salmon translating into us effectively putting some giant protein shake out in the saltchuck for SRKWs to snarf down.

“Each year the sport, commercial and tribal fishing industries catch about 1.5 million to 2 million chinook in U.S. and Canadian waters, most of which swim through the home waters of the southern resident orcas,” Westneat writes. “The three pods in question … are estimated to need collectively on the order of 350,000 chinook per year.”

Fair enough that 350,000 represents their collective dietary needs.

But not only do the SRKWs already have access to those 1.5 million to 2 million Chinook, the waters where they’re primarily harvested as adults by the bulk of fishermen are essentially beyond the whales’ normal range.

For instance, the Columbia River up to and beyond the Hanford Reach, and in terminal zones of Puget Sound and up in Southeast Alaska.

Pat Patillo is a retired longtime state fisheries manager who is now a sportfishing advocate, and he tells me, “If not caught, those fish would not serve as food for SRKWs — they wouldn’t turn around from the Columbia River, for example, and return to the ocean for SRKW consumption!”

“They already swam through the orcas’ home waters and they didn’t eat them,” he said.

WHILE BEARDSLEE IS TRYING TO COME OFF as some sort of orca angel — “It’s like if you’re having a heart attack, your doctor doesn’t say: ‘You need to go running to get your heart in better shape.’ Your doctor gives you emergency aid right away,” he tells Westneat — he’s more like an angel of death trying to use SRKWs as latest avenue to kill fishing.

Type the words “Wild Fish Conservancy” into a Google search and the second result in the dropdown will be “Wild Fish Conservancy lawsuit.”

WFC is threatening yet another, this one over National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration oversight of West Coast salmon fisheries through the lens of the plight of orcas.

It’s not their usual target, which is hatchery production.

Hatchery production, which is the whales’ best short- and medium-term hope.

After WFC sued WDFW over steelhead, a state senator hauled them before his committee in 2015 and pointedly asked their representative at the hearing, “Are there any hatcheries you do support in the state?”

“There are several that have closed over time,” replied WFC’s science advisor Jamie Glasgow. “Those would be ones that we support.”

That sort of thinking is not going to work out for hungry orcas, given one estimate that it will take 90 years for Chinook recovery goals to be met at the current pace of restoration work in estuaries.

And it leaves no place for efforts like those by the Nisqually Tribe to increase the size of those produced by their hatchery to provide fatter fare for SKRWs.

I’m going to offer a few stark figures here.

The first is 275 million. That’s how many salmon of all stocks that the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife produced at its hatcheries in 1989, according to The Lens.

The second is 137 million. That’s how many WDFW put out in 2017, the “lowest production year ever,” per the pro-biz online news source.

The third is 56 million. That’s how many Chinook smolts the agency released in 1989, according to figures from the state legislature.

And the fourth is 28 million. That’s how many were in 2016.

Now, I’m not going to suggest that 50 percent decreases in releases are due entirely to Beardslee et al — hatchery salmon reforms and state budget crunches play the strongest roles.

Nor am I going to suggest that they’re the sole reason that our orcas are struggling — pollutants and vessel disturbance have been also identified as affecting their health and ability to forage.

But with SRKWs dying from lack of Chinook to eat and Puget Sound’s wild kings — which are largely required to be released by anglers — comprising just a sixth to a twelfth of the Whulge’s run in recent years, surely the man must now have some qualms about his and similar groups’ anti-hatchery jihad, including against key facilities for SRKWs on the Columbia?

A FAR BIGGER PROBLEM THAN FISHERMEN for SRKWs is pinnipeds eating their breakfast, lunch and dinner.

Bloated numbers of harbor seals were recently estimated to annually eat an estimated 12.2 million Chinook smolts migrating out of Puget Sound, roughly 25 percent of the basin’s hatchery and wild output, which in the world of fisheries-meets-math science, translates to 100,000 adult kings that aren’t otherwise available to the orcas.

Unfortunately, managing those cute little “water puppies” is realistically way down the pipeline, at least compared to recent lightning-fast moves (relatively speaking) in Washington, DC, that finally gave state and tribal managers the authority to annually remove for five years as many as 920 California sea lions and 249 Steller sea lions in portions of the Columbia and its salmon-bearing tributaries.

By the way, guess who fought against lethally removing sea lions gathered to feast on salmon at Bonneville?

Beardslee and Wild Fish Conservancy.

“Given the clamor surrounding sea lions,”they argued in defense of a 2011 federal lawsuit to halt lethal removals at the dam, “you might guess that sea lions are the most significant source of returning salmon mortality that managers can address. Guess again. The percentage of returning upper Columbia River spring Chinook salmon consumed by California sea lions since 2002, when CSL were first documented at Bonneville Dam, averages only 2.1% each year.”

Three years later, sea lions ate 43 percent of the entire ESA-listed run — 104,333 returning springers.

Whoops.

Those fish were recently identified as among the top 15 most important king stocks for SRKWs.

Double whoops.

So to bring some of the above sections together, as CSL, Steller sea lion, harbor seal and even northern resident killer whale consumption of Chinook in the northeast Pacific has risen from 5 million to 31.5 million fish since 1970 and hatchery production has halved, the all-fleet king catch has decreased from 3.6 million to 2.1 million.

We aren’t the problem.

No wonder that sportfishing rep told me, “We were successful in getting the target off of our backs blaming fishing” for this blog and which Westneat included in his column (I do appreciate the link).

SO INSTEAD OF SHUTTING DOWN FISHING, what could and should we do to help orcas out in the near-term?

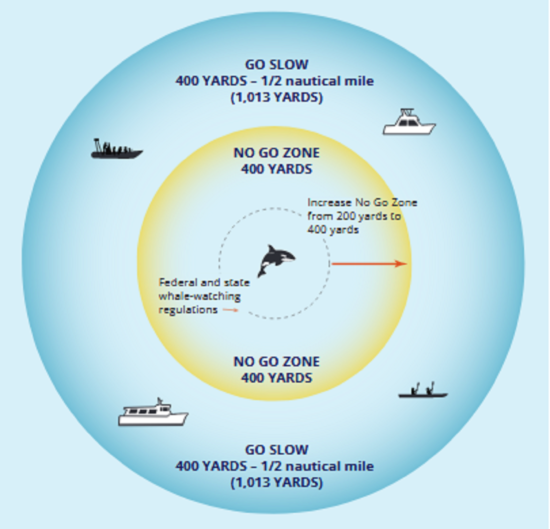

I think the governor’s task force came up with a good idea on the no-go/go-slow boating bubble around the pods. That protects them where they’re eating, and it doesn’t needlessly close areas where they’re not foraging for fish that won’t be there when they do eventually show up.

While I’ll be following the advice Lorraine Loomis at the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission gave after similar sentiments came up last fall — “If you love salmon, eat it” — anglers can take voluntary measures themselves. Even if it’s probably already past the gauntlet of orca jaws, if it makes you feel better to do so, go ahead and release that saltwater king you catch this summer, like Seattle angler Web Hutchins emailed me to say he’s vowing to do.

Switch your fishfinder frequency from 50 kHz to the less acoustically disturbing 200 kHz for killer whales if they happen to show up in your trolling lane.

Pay attention to fish counts and if a hatchery is having trouble meeting broodstock goals, maybe fish another river or terminal zone, or species.

Follow Orca Network on Facebook for where the pods are so you can avoid them.

I also think Beardslee and WFC could, say, lay off their low-hanging-fruit lawsuit schtick (lol, fat chance of that) to give (furloughed) federal overseers time to process permits that ensure hatcheries and fisheries are run properly, instead of having to drop their work and put out the latest brushfire they’ve lit.

And I think boosting hatchery Chinook production is huge, and all the more important because of the excruciatingly slow pace that habitat restoration (which I’m always in favor of) produces results.

Yes, it will take a couple years for increased releases to take effect.

But the ugly truth we’re learning here is, we cannot utterly alter and degrade salmon habitat like we have with our megalopolis/industrial farmscape/power generation complex that stretches everywhere from here to Banff to the Snake River Plain to the Willamette Valley and back again and realistically expect to turn this ship by just pressing the Stop Fishing button and have orcas magically respond.

That’s not the answer.

In this great effort to save orcas, we the apex predator have in fact been forced to look at ourselves in the mirror, at what we’ve wrought, and it is ugly.

We have made a monumental mess of this place and hurt a species we never meant to nor deserved to be.

So we’re setting this right.

It is going to take time. We are going to lose more SRKWs. But we will save them, and ourselves.